When Traffic Itself Becomes the Manager Professor Bernhard Friedrich and Andrea Thiele on the Research Training Group 1931 "SocialCars

Avoiding traffic jams, improving traffic flow, reducing environmental pollution and increasing traffic safety – these are the goals of urban traffic management. But how can the individual players in road traffic make optimum use of the transport network so that these goals are achieved? This is the core question in the Research Training Group 1931 “SocialCars – Cooperative (de)centralized traffic management” in the Core Research Area “Future City” at Technische Universität Braunschweig. Bianca Loschinsky spoke with Professor Bernhard Friedrich, head of the Institute of Transportation and Urban Engineering and speaker of the Research Training Group, and coordinator Andrea Thiele about the research in the interdisciplinary Research Training Group.

Professor Bernhard Friedrich, spokesperson of the Research Training Group SocialCars. Picture credits: Markus Hörster/TU Braunschweig

Professor Friedrich, the Research Training Group 1931 bears the name “SocialCars”. What does “social” mean in this context?

Prof. Friedrich: First of all, “social” means ensuring the participation of everyone in mobility. In this context, “cars” refers not only to car traffic, but to mobility as a whole. This includes public transport and also cycling. The human being as a traffic participant is placed at the centre of attention.

What is the idea behind a cooperative (de)centralized traffic management?

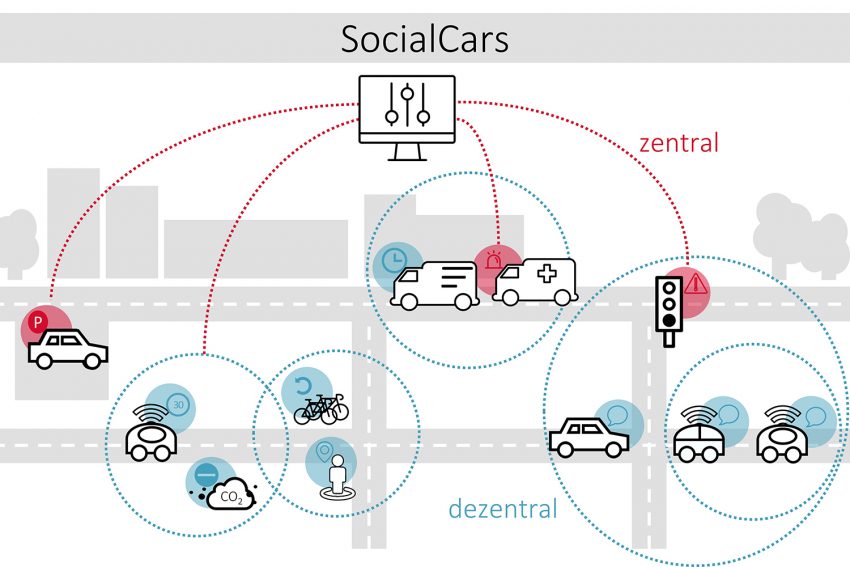

Prof. Friedrich: Research in the Research Training Group examines the interaction of central (system-optimal) control and decentralized (user-optimal) action and the development of dynamic models that take both views into account.

The focus is on the interaction of individual freedoms (decentralized), but within a space that is being centrally mediated. In the simplest case, this space can be the road traffic regulations. But depending on the situation, it can also be guidelines from the traffic management center, according to which one can act locally: Access restrictions or even privileges, such as speed limits and prohibiting turns.

One example: If, at certain points, pedestrians and cyclists appear to be a larger group than motor vehicle traffic, this group tends to be privileged, priority is given to them and traffic around them is slowed down.

Traffic itself is very complex. To what extent can traffic be planned and controlled at all?

Prof. Friedrich: You have to control and plan traffic. The planning level is long-term and forms the basis of the transport system, like the transport networks of roads and railways. How traffic develops is a socio-political process. There is a development in the cities from a car-friendly city to a traffic-friendly city to a city-friendly traffic to traffic calming. These developments are an expression of the social decision-making process.

They include the rather dynamic control, by which we understand traffic management today: Traffic lights or speed displays, which are used to influence traffic, right down to the vehicles, which provide drivers with information on the best route to take so that they don’t get stuck in traffic jams or are able to drive more smoothly.

Or when, for example, a high concentration of pollutants is measured and short-term measures are initiated to counteract this, such as changing the route or restricting access.

What role do changes in traffic, which are also the result of social decision-making, play in research within the Research Training Group?

Prof. Friedrich: We have various topics that deal with cycling, shared space or public transport. One question, for example, is: How can public transport networks be optimised, also using new mobility offers, so that they become more flexible and attractive and perhaps also cheaper? Although we have defined a broad topic area overall with SocialCars, the search for the doctoral topics of the individual doctoral students is individual.

Andrea Thiele, coordinator of the SocialCars Research Training Group. Picture credits: Isabell Massel/TU Braunschweig

How many doctoral students are currently participating in the Research Training Group?

Thiele: In the Research Training Group we currently have twelve doctoral candidates, twelve associated doctoral candidates and two DAAD scholarship holders. Two doctoral candidates are doing research at each of the institutes participating in the Research Training Group. Many of the doctoral students are currently on the final stretch to completing their dissertation. Since the beginning of the Research Training Group, a total of 14 doctorates have been completed.

We are particularly delighted that we have a balanced ratio of female and male doctoral students.

Our Research Training Group is also very international: around 50 percent of the doctoral students come from other countries, including China, India, Bangladesh, Serbia, Albania, Syria, Romania, Chile and Brazil.

The research training group is concerned with the question of how the individual players in road traffic can make optimal use of the transport infrastructure so that safety is increased and traffic jams and environmental pollution are avoided. Are there any findings on this subject yet?

Prof. Friedrich: Of course, research in the Research Training Group is initially base-oriented. However, methods are associated with these fundamentals, which we can also use in practice. I am thinking, for example, of a method developed by a doctoral candidate: the optimisation of public transport networks using mobility services. Various studies also deal with traffic demand modelling. Based on population structure data of cities, the traffic demand is determined using agent-based systems. This means that the total population of a city is modeled synthetically. Each agent, i.e. each person, has an activity plan that corresponds to real conditions. This creates traffic. This is simulated on the available traffic networks so that the route and means of transport are depicted realistically. You can read a lot from these models, for example: What is the benefit of introducing a new mobility offer – such as car sharing or ride sharing? What are the limits of the prices that can be charged for them? How great are the social benefits or also the social costs? One of our graduates is now working in industry on transport demand models for commercial applications. This is a one-to-one transfer, so to speak. Of course he is not taking the software with him, but his knowledge.

Interaction of central and decentralized traffic management strategies in SocialCars. Picture credits: SocialCars/TU Braunschweig

How can social and individual interests be given equal consideration in the management of transport?

Prof. Friedrich: Balancing is indeed difficult, it is an ongoing negotiation process. The planning level provides the framework. Balancing then takes place locally on an event-driven basis, for example when a public transport vehicle is given priority at a traffic light or through an extra bus lane.

Traffic has the advantage that it can be observed, but it is very dynamic and spatially distributed. It is difficult to capture it in its entirety with measuring instruments. The measurement is only possible locally at different places. To draw conclusions from these local measurements about the big picture is also a challenge, which is often a topic in the dissertations.

For example, we supplement local observations with motion data, so-called floating car data or location-based services data obtained from smartphones, and thus obtain a complete picture of the traffic flow over space and time. We also use the data to reconstruct the means of transport used by people on the move.

The Research Training Group’s research programme consists of six research areas, which are grouped into three research fields: Psychological and economic drivers/influencing factors, (de)centralized cooperative traffic management and technological drivers/influencing factors. The Research Training Group is thus very broadly based.

Prof. Friedrich: The range of our research is very broad because we work on a strongly interdisciplinary basis. With the Research Training Group, we have definitely improved cooperation across disciplines. We have built a small bridge from traffic planning to traffic psychology or even to communication technology and geoinformatics.

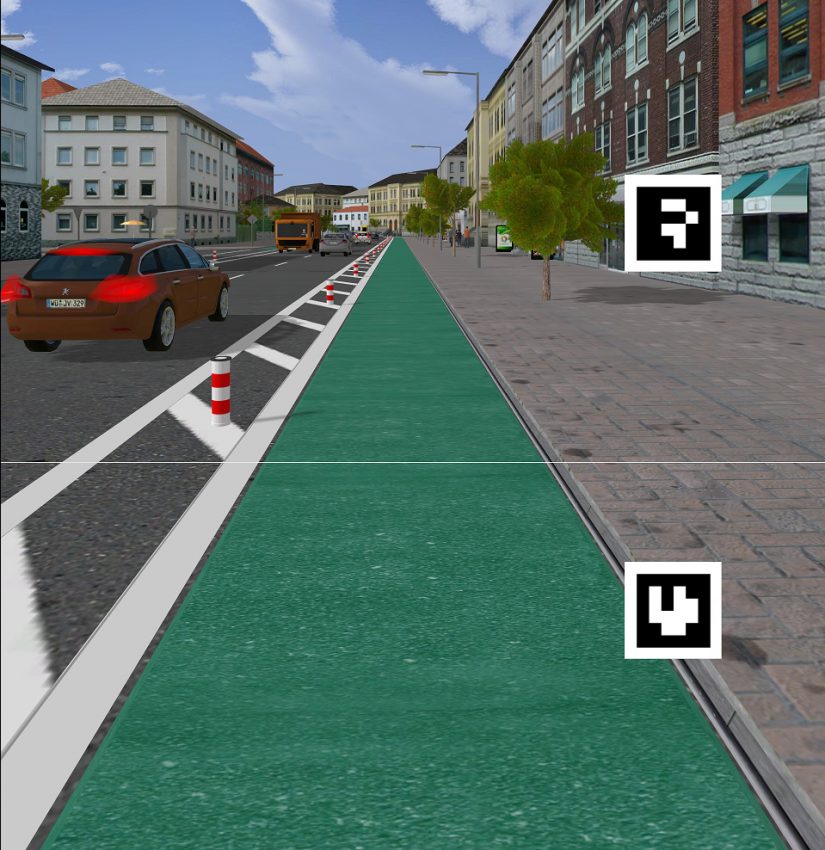

Eine geschützte Radspur im Fahrradsimulator. Bildnachweis: SocialCars/TU Braunschweig

Research field A is thus concerned with the individual, the human being, the road user as a car driver and cyclist. In this research area, the colleagues around Professor Mark Vollrath from the Institute of Psychology, Engineering and Traffic Psychology are concerned with questions of route choice, among others: How do individuals make decisions, how can they be supported in doing so? And further: How do they feel in automated vehicles? Where are the limits?

The researchers around Professor Dirk Mattfeld of the Institute of Business Information Systems, Department Decision Support, are dealing with decision support in the field of logistics and the integration of shared mobility systems in urban traffic.

What are the other research fields concerned with?

Research field C deals with the technological drivers, in particular with car-to-x communication and dynamic maps and map services. These two areas of the Research Training Group are represented by the Institute of Cartography and Geoinformatics at Leibniz Universität Hannover (Prof. Monika Sester) and by the Institute of Communications Technology at Leibniz Universität Hannover (Prof. Markus Fidler). We have interesting joint projects in which we combine traffic flow simulations with communication simulations embedded in city models. We can simulate which information can or cannot be passed on from which road user to the other, if the radius is restricted by the structural conditions.

Field B deals with centralized and decentralized traffic management. Here, the Department of Informatics of TU Clausthal under the direction of Prof. Jörg Müller and our Institute of Transportation and Urban Engineering conduct research. The main focus is on modelling traffic and transport demand. In traffic flow and interaction models, for example, we depict what happens when a pedestrian hits a car: who swerves and how? Does it get crowded? Which speeds are driven? What kind of traffic jams occur? Based on these models, we can design optimisation strategies for traffic management. For example, one dissertation dealt with analysing which left-turning vehicles should be prohibited in a traffic network for reasons of safety and efficiency.

Researchers from almost all disciplines worked on the joint project “Cooperative Parking Lot Search”. What was the project about?

Parking spaces have something very dynamic about them, they are sometimes free, mostly occupied. If I don’t need one, I often drive past a free parking space that someone else needs, but does not know about. The aim of the interdisciplinary project was to distribute this information in such a way that there is as little traffic as possible in search of a parking space. A classic simulation-optimisation project: In a synthetic traffic network we simulated traffic, including parking procedures and free parking spaces. New technologies in vehicle communication (vehicle-to-vehicle as well as vehicle-to-infrastructure) could enable drivers to exchange information about their search for a parking space and thus make the search more efficient. The interdisciplinary project was very well suited to bring together competences from the different disciplines and increase understanding.