Tiny neighbours that pack a punch Institute of Geosystems and Bioindication shows microorganisms in the Hagenmarkt living lab

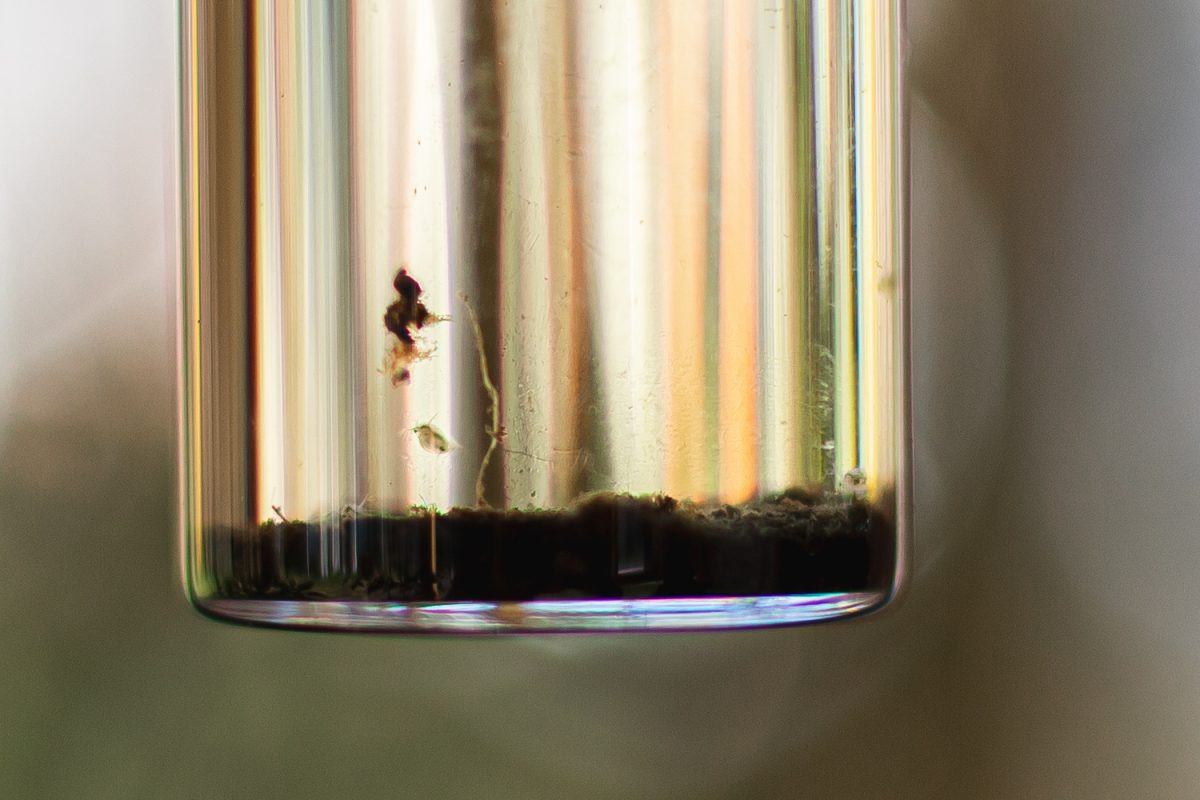

At first glance, only water is visible in the test tubes. A little cloudy perhaps in some places, but otherwise nothing special. But inside the containers are tiny creatures that pack a punch. Dr. Liseth Pérez, a research associate at the Institute of Geosystems and Bioindication (IGeo) at TU Braunschweig, has filled the jars with aquatic bioindicators for an exhibition in the Hagenmarkt living lab. She explained to us on site what they are and what scientists can study with them.

Dr. Liseth Pérez is a research associate at the Institute of Geosystems and Bioindication (IGeo) at TU Braunschweig. Photo credit: Max Fuhrmann/TU Braunschweig

After Liseth Pérez has moved the test tubes a little, you can discover them: Tiny animals move through the water. In some containers are ostracods, in others water fleas. The aquatic creatures are no larger than four millimetres. Today, the scientist from the IGeo has not only brought them fresh water, but also a treat: small spinach. “The plant contains many minerals that are important for the animals,” says Liseth Pérez. Every three to four days they are fed and get new water.

These microorganisms can also be found in urban areas, for example in rain barrels and in small puddles if they do not dry out too quickly. Or in flower pots with water plants in the Botanical Garden and in a pond in the Östliches Ringgebiet of the city of Braunschweig. This is where the water fleas and ostracods on display come from, which Liseth Pérez collected together with Mauricio Bonilla, a doctoral student at the IGeo.

Guide fossils for the determination of rock layers

The ostracods have seven pairs of extremities with which they can swim, run, swirl and preen. They usually live on or in the mud or climb around on plants in the shore area. Their life cycle lasts from a few weeks to a few years. The organisms are important guide fossils in classical geology, as they can be used to determine the relative ages of different rock layers.

Water fleas are found in all freshwater habitats. They live mainly in the shore area on water plants or in the sediment. Depending on the environmental conditions, they reproduce in different ways: For most of the ice-free season, they reproduce asexually by cloning females. Only when worsening conditions cause stress in autumn do males and reproductive females emerge and the water fleas switch to sexual reproduction and form permanent eggs. These eggs, also called resistant eggs, can survive for a long time under adverse conditions, for example at low temperatures or during dry periods.

Reconstruction of climate changes

And what makes ostracods and cladocerans, as the water fleas are scientifically called, so-called aquatic bioindicators? The small aquatic creatures react sensitively to changes in their environment, for example in temperature, oxygen concentration, salinity or the pH value of the water in which they live. This allows the researchers to use them to reconstruct current and past changes in biodiversity, water quality and climate. “If organisms suddenly die or species assemblages change, that is, the group of different species in the same ecosystem, we know that something has changed in the environmental conditions,” says Liseth Pérez. Fossil bioindicators are found, for example, in lake sediments, which the IGeo team examines after deep drilling in Germany, but also in Tibet and North and Central America.

“The little organisms pack a powerful punch.” Liseth Pérez continues to feed the little animals. They are something like a weather station from the past. “In our research, we always look for analogy in the past to make predictions for the future.” The scientists can also bring back to life permanent eggs of ostracods and water fleas from 200-year-old sediment layers with a little water and analyse genetic changes.

After the exhibition in the living lab, the water fleas and ostracods will be passed on to the Zoological Institute of TU Braunschweig. Professor Miguel Vences from the Department of Evolutionary Biology will then examine the organisms genetically.