The key to digital and sustainable construction TU Braunschweig research team on the "Digital Construction Site"

Resource efficiency, fewer emissions, shorter construction phases, improved occupational safety – what sounds like a potpourri of wishes for the construction industry could soon be a reality thanks to the “Digital Construction Site”. With this project, researchers want to identify possibilities for a future construction site infrastructure and also involve the regional and national economy. Companies were given a first insight into the project on 11 April at the “Additive Manufacturing/3D Printing” innovation forum organised by the TransferHub of TU Braunschweig and Ostfalia University, Braunschweig Zukunft GmbH and the Braunschweig Chamber of Industry and Commerce. We spoke to the “Digital Construction Site” research team about their vision for the future, a new look for buildings, changes for skilled workers and challenges for building materials.

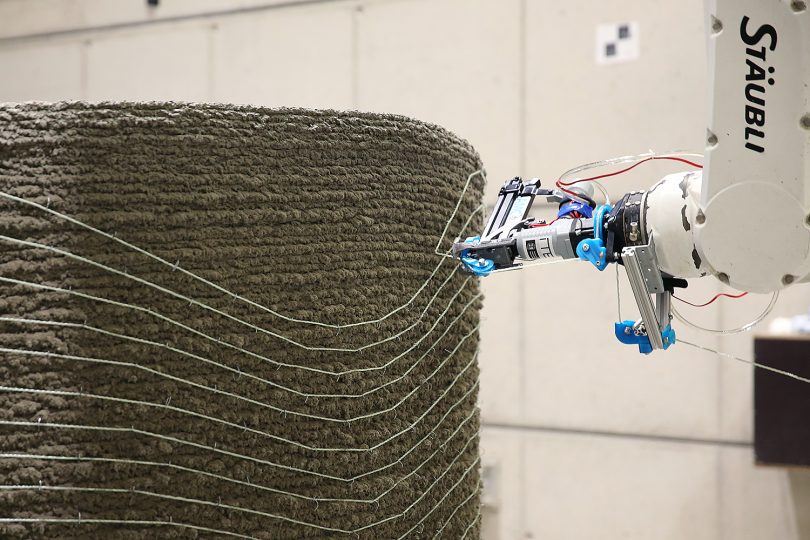

A digital construction site similar to the one at TU Braunschweig could become a reality in the future. Photo credit: Tjark Spille/Institute for Structural Design

When you think of the “Digital Construction Site”, the first thing that comes to mind is 3D printed houses. But what exactly is behind this?

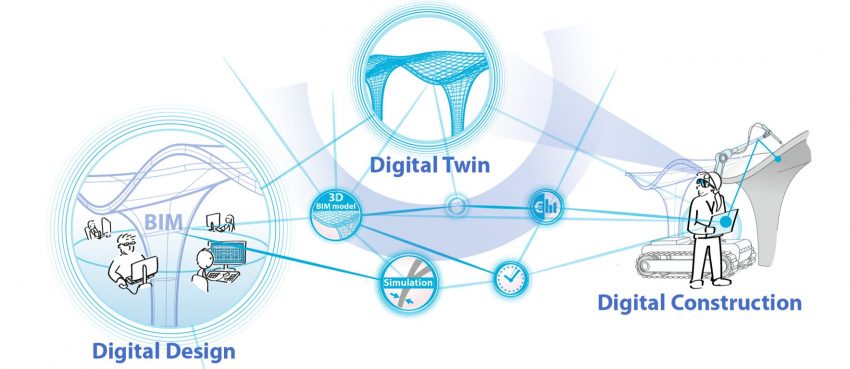

Prof. Harald Kloft: The end-to-end digitalisation of construction is the key to leading the construction industry into a productive and sustainable future. While powerful software is available for planning and the use of digitally controlled components in construction is progressing at full speed, the construction site is still largely organised in a traditional, manual way. The exchange of information with construction sites is therefore generally document-based, often still in the form of printed plans. The digitisation of construction sites is therefore the link to achieving end-to-end digital process chains – from planning and execution to the operation of buildings. And 3D printing is a key digital technology in this context. Why? 3D printing enables automated, digitally controlled processes that were previously only known from mass production, while at the same time enabling individualised, material-efficient and low-waste production. This makes 3D printing ideal for the construction industry, as it brings together economic, environmental and social aspects, such as the reduction of physical stress.

At the “Digital Construction Site”, we will initially focus our research on the digital interfaces between design and production, and test 3D printing with concrete, but also with steel and clay, under real-life conditions on a 1:1 scale. We have a stationary gantry printer, several mobile robots, tracking systems and immersive technologies. Two things are particularly important to us in the digitalisation of the construction site: firstly, the work processes that can be used to pursue innovative approaches to construction production. In the construction industry, we are used to sequential processes. First we plan, then we build – ideally exactly as planned. Sometimes, however, technical imperfections are only discovered after the fact and the design cannot react to them. With digital construction processes, we can use sensors to monitor production. This provides us with constant information on the progress of construction, which we can feed back into the planning process. This interaction between planning and production means that planning measures can be taken immediately in the event of deviations. The second point relates to working conditions. We believe that people will continue to play a central role on construction sites, but I am sure Mr. Schwerdtner can tell you more about this.

Professor Schwerdtner, how is the “Digital Construction Site” changing work on site?

Prof. Patrick Schwerdtner: In order to integrate people into digitally organised construction sites, job profiles will have to change significantly. You will no longer (only) need skilled workers to carry out manual tasks. New areas of work are emerging that require different knowledge and skills. With augmented reality (AR), people will be able to participate in digital manufacturing processes at any time. The result will be high-quality jobs with higher standards of health and safety, and a new appeal for construction careers.

However, every construction site is different and projects require digital processes to be adapted to the specific conditions. A complete replacement of manual labour by robotic systems is currently difficult to imagine.

In the past, people would have warned against these developments, arguing that they would put jobs at risk. Today, companies are aware that, in the medium to long term, there will not be enough labour available to meet the major challenges in the construction industry using traditional production methods. This is why the development of robotic systems, on the one hand, and the optimisation of conventional processes through digital methods, on the other, must be aimed at increasing labour productivity.

The “Digital Construction Site” will not only change the way we work. What impact could the digital construction site have on the appearance of buildings?

Prof. Norman Hack: The design language of 3D printed architecture will evolve over time, just as many other building materials and techniques have in the past. The transition from wood to stone in ancient Greek architecture is a fascinating example of how technological and material advances in construction do not necessarily lead to an immediate departure from established aesthetic and structural norms. Instead, there is often a blending of the new with the traditional, reflecting a complex interplay between innovation, tradition and practicality in architectural development.

What is clear, however, is that we are no longer bound by right angles and that wall structures no longer need to be solid. With 3D printing, we can print material where it is actually needed structurally.

When it comes to climate protection and sustainable development, what contribution can digitalisation on the construction site make?

In addition to the stationary gantry printer, several mobile 3D printers are also available. Photo credit: Tjark Spille/Institute of Structural Design

Prof. Dirk Lowke: Our building infrastructure has an inglorious peak in CO2 emissions due to its production and operation. It is important that we design buildings in such a way that they use fewer resources during construction, have the longest possible service life and require less energy during operation. When it comes to material efficiency, additive manufacturing can make a significant contribution, for example by not having to fill the entire formwork for a component with concrete, but instead – as Mr. Hack mentioned – printing the concrete only where it is structurally required. In this way, we can save up to 70 per cent of the resources required. Of course, we are also interested in exploring additive manufacturing with new building materials that have significantly lower CO2 emissions, such as clinker-reduced eco-concretes or geopolymers.

Sustainability also has economic and social components. Economic sustainability means that we increase productivity and achieve the goal with fewer resources, making it cheaper in monetary terms. This means that only those production processes will survive that are economically viable in the medium to long term. The “Digital Construction Site” is the right approach, because in the future we will simply have too few resources – both in terms of labour and materials.

We see social sustainability primarily in the areas of occupational health and safety. By using additive manufacturing and other digital technologies, the physical strain on skilled workers on the construction site is reduced and people can work longer. This is particularly important as our summers get hotter and hotter, and working on construction sites can only be done with very limited productivity because more breaks are needed or work has to be done at off-peak times. The machines are not quite as important as the heat.

What building materials other than concrete should be used in the project? What are the particular challenges?

Prof. Dirk Lowke: In addition to printing concrete, it is also possible to 3D print with less CO2-intensive building materials such as clay. However, this natural material is more difficult to control than the highly standardised and standardised building material concrete. Particular challenges include the structural build-up during printing, shrinkage during drying and the lower compressive strength and durability of earth-based materials.

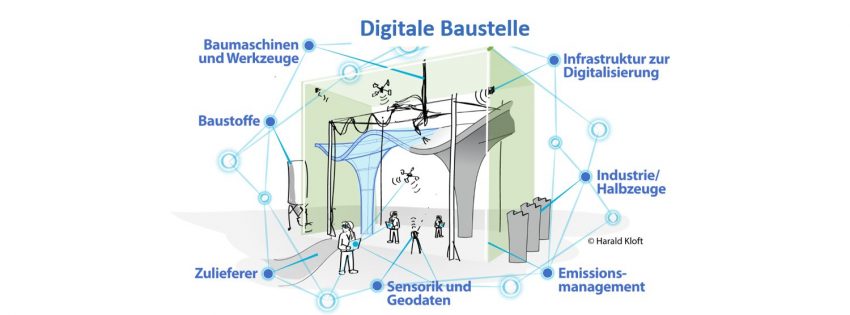

Various digital technologies are brought together and networked on site in the spirit of Industry 4.0. Photo credit: Harald Kloft/TU Braunschweig

On-site and in-situ printing – what are the differences and how should they be implemented in the “Digital Construction Site”?

Prof. Norman Hack: In-situ printing is a concept where the part is made on site and remains there after printing. The component is not moved after printing. This strategy is particularly suitable for vertical components such as walls and columns.

On-site printing, on the other hand, means that a component is printed on site, but then has to be moved into its final position. The field factory can be used as a reference here. In the context of the “Digital Construction Site”, one could imagine, for example, horizontal ceiling elements being printed by mobile robots in a section next to the actual building and only being lifted onto the walls once they have hardened. This would allow parallel production and speed up construction.

Professor Gerke, you are working on surveying sensors in this project. Is this already being used on construction sites? And what changes do you see in the context of the “Digital Construction Site”?

Prof. Markus Gerke: On “traditional” construction sites, surveying is used at certain stages of production, for example when setting out building axes or when taking detailed measurements for the integration of certain components. With manual construction methods, geometric construction errors can be compensated within certain tolerances.

On the “Digital Construction Site”, however, a deep integration of modern, high-precision surveying sensors and methods is required in all work steps. For example, the automated construction processes on site need to be checked for correct positioning. It is also necessary to ensure the quality of the manufactured parts close to the printing process so that subsequent processes can be optimally controlled, as it is not possible to manually correct components afterwards. Other interesting research questions relate to the full integration of these technologies, even in different weather conditions on the construction site, or ensuring safety at work by tracking all the players so that “man and machine” can work together optimally.

Ideally, a digital process chain is created that increases the degree of automation. Photo credit: Harald Kloft/TU Braunschweig

Do you see drones on construction sites in the future?

Prof. Markus Gerke: We have been researching methods for a long time to efficiently and accurately record the geometry of buildings and building parts using flying robots equipped with cameras or laser scanners. Since all planning data and construction details are available in digital form, the use of autonomous flying systems is also being considered for the “Digital Construction Site”. For this reason, we have purchased a powerful drone and will be investigating its use. The combination with terrestrial sensor technology is interesting, as we can get an overview of the whole site from all perspectives.

What could be one of the first research projects on the “Digital Construction Site”?

Prof. Norman Hack: As part of our Collaborative Research Centre TRR 277 “Additive Manufacturing in Construction” (AMC), we have been working with the Technical University of Munich for the past four years on important fundamentals for large-format 3D printing. So far, most of the tests have been carried out in the laboratory. Now it is time to move out of the lab and into the real world of the construction site. This step raises completely new research questions, which we will investigate in depth in some of the subprojects of the second phase of the SFB, in addition to important sustainability issues.

We are also working with our European research partners Mesh AG from Switzerland, Rupp Gebäudedruck from Germany and COBOD from Denmark on the Horizon Europe project “Next Level AM”. Here we want to bring 3D printing of shotcrete with automated reinforcement production to the construction site to build multi-storey buildings.

The project should also be application-oriented. Will the building industry be involved?

Prof. Patrick Schwerdtner: Absolutely. We invite the regional and national construction industry to participate in our research projects – whether as a partner for discussing technical issues and areas of application for further development, or for dialogue formats to present visions of future-oriented construction production. After all, it is important for corporate strategy to initiate a transformation process towards digitalisation in good time. We are making a clear offer to the industry to get involved in the project. We are also tackling problems on the ground that may not have existed in the laboratory.

The last question: When could the “Digital Construction Site” become a reality?

Prof. Harald Kloft: We can start right away. You shouldn’t think of the “Digital Construction Site” as an end product that will only be available in five to ten years’ time. Although we are researching the “Digital Construction Site” with high-tech equipment right from the start, our approach to transferring it to construction practice is to gradually integrate it into the existing construction site infrastructure. For example, manual processes could already be supported by augmented reality. Or 3D printing could be combined much more flexibly with formwork-based concrete construction.

For example, we have developed a construction technique that allows us to cast much thinner slabs and print ribs for reinforcement. This reduces the mass of concrete by almost 60 per cent. But, as Professor Schwerdtner said earlier, we also need the construction industry to be willing to innovate. Only by working together can we ensure that the construction industry is properly perceived by politicians and society as one of the areas of the future in which it is important to invest. The construction industry covers the basic needs of human coexistence, such as the need for living space. Only with new technologies will it be possible to meet the basic needs of building and infrastructure in an economically and ecologically sustainable way.