“The Arctic makes me feel alive” Why doctoral student Emma Cameron enjoys working in extreme conditions

Many people curse the cold season. Emma Cameron, on the other hand, enjoys it so much that the doctoral student at the Institute for Geosystems and Bioindication at Technical University of Braunschweig regularly sets off on expeditions to the Canadian Arctic. Neither frostbite nor equipment failure can stop her from taking sediment samples in the ice.

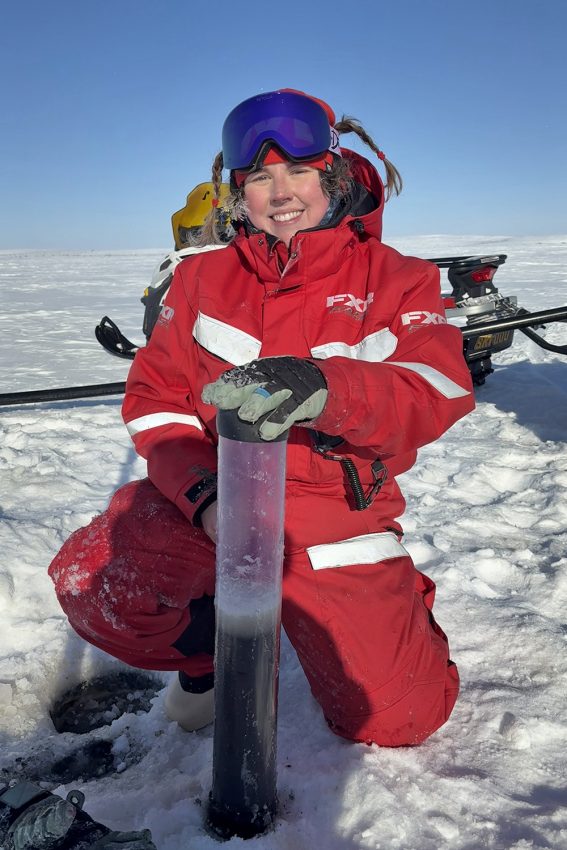

March 2025, Mackenzie Delta region, Canadian Arctic: Emma Cameron stands in the middle of a frozen lake, facing a hole in the ice. Slowly, she lets a rope slip from her hand into the dark water – along with a heavy piece of equipment, a sediment corer. Similar to a drill penetrating a porous wall, it penetrates deeper and deeper into the bottom of the lake.

Emma Cameron with a sediment core shortly after sampling. Picture credit: Moritz Langer/Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

The sediment accumulates layer by layer in a tube. Once the corer is at the desired depth, Cameron pulls it up with all her strength. A valve closes at the top of the tube, creating negative pressure. This keeps the sediment core intact – but only until it breaks through the surface of the water.

To prevent the sample from being lost, Cameron resorts to an unusual method: she dips her bare hands into the water and seals the tube shut with a cap. “At around one degree Celsius, the water isn’t the biggest problem,” she says. “The air is minus 40 degrees. When I pull my hands out of the lake, I can see the water freezing on my skin within seconds.” As soon as the corer is pulled out of the lake, everything has to happen quickly. It is only once the sample is secured that the scientist slips into prepared gloves containing heat pads.

Back in the comparatively warm Braunschweig, the doctoral student at the Institute for Geosystems and Bioindication reports on the sampling at the bottom of Arctic lakes. For her, the sediment cores are more like treasure than mud – they are archives of the environmental history of the Arctic.

A journey through time into the climate of the past

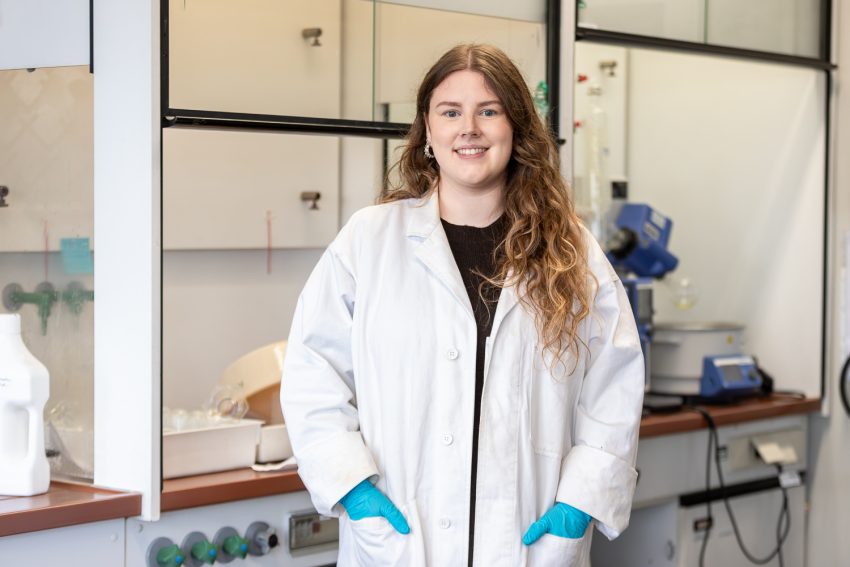

In the laboratory at TU Braunschweig, Cameron analyses the remains of small animals and algae that are left behind in the sediment and can provide clues about salt and ice conditions. She is also interested in identifying which chemical substances are present in the sediment – particularly residues from earlier exploratory drilling for oil and gas. In the Canadian Arctic, extensive exploration for such resources took place throughout the last century. The resulting waste products are still stored in pits in the permafrost, so-called drilling mud sumps. “As the Arctic is experiencing climate change faster than anywhere else, permafrost is thawing rapidly, and toxic drilling fluids may migrate into nearby waters,” explains Cameron.

At the Institute for Geosystems and Bioindication, Emma Cameron is researching how the environment of Arctic lakes has changed over the last hundred years. Picture credit: Kristina Rottig/TU Braunschweig.

In the Arctic improvisation is part of everyday life

There, they work closely with the Arctic community. This benefits both sides equally. “When my GPS failed due to the cold, I wouldn’t have been able to find my way around the endless white, flat landscape without the help of my local colleagues,” recalls Cameron. Without this support, targeted sampling would have been virtually impossible. Furthermore, they wouldn’t have seen half as many wild animals.

All of this is only possible because Cameron and the rest of the “ThinIce” team is willing to work under conditions that go far beyond normal everyday research. She is fascinated by the extreme temperatures, the abundance of unanswered research questions, and the unpredictability of each day. “You always need a Plan B, and usually a Plan C as well,” says the doctoral student. When her original corer froze, she and a colleague quickly constructed an alternative using plumbing pipes purchased from the local hardware store. The method worked surprisingly well. “At minus 40 degrees, our technology is sometimes simply unusable,” says Cameron. “Then you have to get creative.”

An extra dose of responsibility

The project is still in its early stages. Therefore, it is not yet possible to make any concrete statements about potential environmental impacts. However, initial physical evidence suggests that the drilling mud sumps are subsiding and that potential flow paths towards the lakes could be forming.

In the long term, the research should help to better assess risks and set priorities for targeted environmental monitoring – especially for the people who have lived in the region for generations.

This is precisely what motivates Cameron: “It’s about the bigger picture: what is happening to these lakes that local communities rely on? This gives the whole project an extra dose of responsibility.” Numerous sediment cores are waiting to be analysed at TU Braunschweig. However, one thing is already certain: this was not her last visit to the Arctic.