Delhi – a fast-developing metropolis full of contrasts Future City Goes Global with Bartek Sawicki

How will the liveable city of tomorrow look like? In order to find answers to this question, scientists from the Core Research Area “Future City” are exchanging ideas with researchers from all over the world. In the series “Future City Goes Global” they take us to other cities, show differences and similarities and report on planned research collaborations. Bartek Sawicki from the Institute of Structural Design gives us an insight into his stay at the “Indo-German Forum on Sustainable Urban Mobility” in New Delhi.

Bartek Sawicki at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, host of the Indo-German Forum. Picture credits: Bartek Sawicki/TU Braunschweig

Mr Sawicki, what was the reason for your trip?

I had a chance to go there for a workshop on “Integrated Engineering for Future Mobility”, where twelve young researchers from TU9 universities met twelve young researchers from Indian Institute of Technology Delhi and Indian Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. The event was organised by the German Centre for Research and Innovation (DWIH) New Delhi within the framework of the “Indo-German Forum: Sustainable Urban Mobility”.

I have spent one week in New Delhi, discussing differences and similarities in research and societal challenges, and thinking how Indian and German researchers can learn from each other.

“One of the examples we discussed are so-called slow zones, quartiers with limited traffic aimed to create a pleasant and human-friendly space for locals. This concept is now being implemented in Europe, US and elsewhere, leading often to creation of transportation corridors and calm enclaves in the middle.”

What research topics did you focus on during your stay?

The group was quite diverse, spanning from those working on batteries for electric vehicles, through autonomous cars, up to urban planning. The goal was to look for non-obvious synergies to tackle mobility-related problems

As civil engineer, I have teamed up with mobility and city planners. We discussed in particular how different the cities in Europe and India are at first sight, but in the same time how similar concepts can be found.

One of the examples we discussed are so-called slow zones, quartiers with limited traffic aimed to create a pleasant and human-friendly space for locals. This concept is now being implemented in Europe, US and elsewhere, leading often to creation of transportation corridors and calm enclaves in the middle. Such a model was historically adopted in India, and especially in New Delhi – with gated zones or large palaces providing safety, and wide streets around them perceived as hostile. Having European cities with traffic distributed uniformly over the city, and Indian cities with their closed communities and unfriendly transport corridors, we can observe the two ends of a spectrum, with an optimum laying probably somewhere in between. This shows that both Europeans and Indians can learn some valuable lessons from each other.

Modern landscape of office district Cyber City in Gurgaon. Picture credits: Bartek Sawicki/TU Braunschweig

What impressed you most in the city?

The variety. In Delhi you can find everything.

Starting with the Old Delhi, with some streets no wider than one meter, shadowed by adjacent buildings even during the day, and ending abruptly with opened door to a small shrine or private flat. With street markets, cows, dogs and rats running around, and people, scooters and rickshaws taking all the available street.

Through the Kartavya Path (called also Rajpath or Kingsway), a British-designed corridor of power, spanning between the Presidential Palace and the India Gate, a barren and shadowless strip of asphalt, almost three kilometres long, designed for parades and, I bet, unbearably hot during the summer months.

“The bus was fully electric! That was just another proof that India is a fast-developing sub-continent full of contrasts.”

Up to Gurgaon (formally a city in neighbouring state, but forming part of Delhi metropolis) with its elevated rapid metro and skyscrapers made of concrete, steel and glass. The business and technology hub, where one can forget whether is in India, Europe or US.

However, my personal highlight about the potential of India was a trip from Agra to Delhi, after visiting the famous Taj Mahal on Saturday, once the official part has ended. We have boarded an intercity bus with Indian tourists getting back to Delhi, on a crowded and littered street without lighting. Inside the bus, seats were extremely comfortable, air conditioning working even too well, and some 250 kilometres long trip took only three hours thanks to the new three-lane highway with tarmac smoother than on some German roads. But, most importantly, the bus was fully electric! That was just another proof that India is a fast-developing sub-continent full of contrasts.

“In Delhi I haven’t seen too many public parking spaces on a street, following the concept: your car – your problem.”

What makes this city special? What could we copy for German cities?

India and Germany have completely different needs and challenges, in particular when I think of how crowded Indian cities are, and how empty and small Braunschweig felt after coming back.

One thing we could copy to Germany is the change of mindset concerning motorized transport. Private cars are not the most efficient mean of transportation in congested cities, and they take unreasonably large amount of space. In Delhi I haven’t seen too many public parking spaces on a street, following the concept: your car – your problem.

Looking at carparks along most of streets in Germany, and vast amount of land they take, I think this is something to be changed.

What is the number one means of transport in the city?

The number one is definitely the Metro. Growing dynamically for last 20 years, the network consists now of nine regular lines, an express line to airport, and two other lines in the grater agglomeration. New sections open every few months.

This fast, air-conditioned and reliable mean of transport is favoured by middle and upper-middle classes, such as employees of public offices in this capital city. Clean and safe, with “check in – check-out” electronic system and multiple interconnecting stations, it allows for travelling quickly and in comfort across the whole city. In every coach there are seats reserved for senior citizens and women. Furthermore, to increase comfort and safety of travelling to women, which is still a problem in India, the first coach is reserved exclusively for them. The “last mile” problem is solved by omnipresent rickshaws. The drivers are awaiting at each metro station for their customers, more and more often in their electric vehicles.

Interestingly, public buses are not considered as a viable mean of transport by the middle class. Despite free admission of women and a first half of each vehicle reserved for them, they are perceived as dangerous, uncomfortable and slow. Hence, the social spectrum of passengers in metro and buses is radically different – something unexpected for Europeans perceiving a public transportation system as a single whole.

What research cooperations are planned?

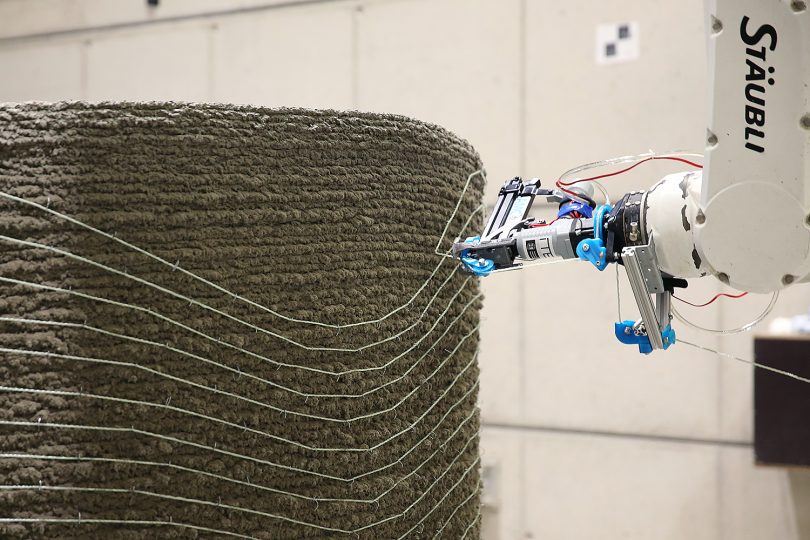

The main goal of the visit and the workshop organized by DWIH was to establish connections and think of new and relevant research questions. What we’ve learned is that the first step in our cooperation should be to understand each other’s challenges and whether the tools to overcome them in one place are feasible in the other. In particular, we would like to check if digital construction methods, such as Additive Manufacturing in Construction, e.g. as developed by our Collaborative Research Center Transregio 277 Additive Manufacturing in Construction (AMC),) provide a viable solution in Indian reality, e.g. for construction of new metro lines. Hopefully this research direction will be able to set-off this year, given that the are many ongoing academic exchange and cooperation programs between Germany and India.