Transnational Teaching TU Braunschweig and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem are researching Red Bread Mold

Fungi are of great importance for biotechnological applications such as the production of pharmaceuticals, fine chemicals or biofuels. But at the same time, as pathogens, they pose a growing threat to plants, animals and humans. To date, however, the molecular mechanisms behind the growth and development of fungi have been little understood. In a joint project, Professor André Fleißner of the Technische Universität Braunschweig and Professor Oded Yarden of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel, are investigating the growth of Neurospora crassa, the Red Bread Mold. Alongside cooperation in research, the focus is also on exchange in teaching.

In the laboratory together: Professor Oded Yarden, Professor André Fleißner and Lucas Well. Picture credits: Anna Krings/TU Braun-schweig

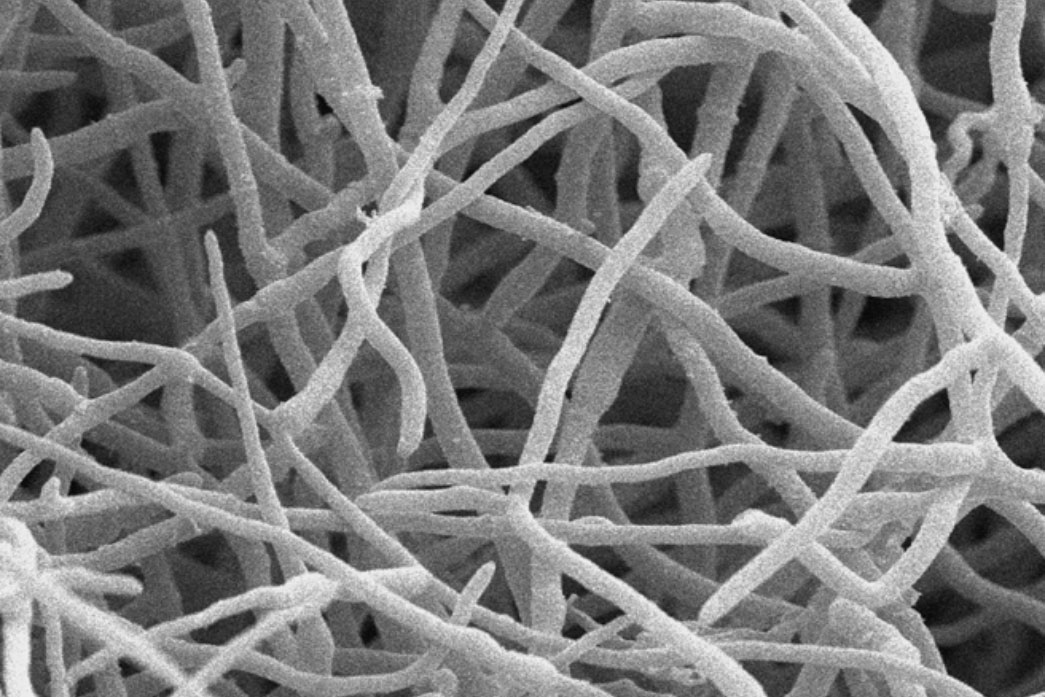

Filamentous fungi, which include the Red Bread Mold, form colonies of multicellular, long filaments. The so-called hyphae can grow in a certain direction and navigate their environment. This directional growth is essential for the reproduction and development of the fungi. They can, for instance, recognise each other, grow towards each other and fuse together to form larger units. “We want to investigate how the fungi know in which direction they grow and how these processes can be manipulated,” explains Professor Oded Yarden from the Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology. “Neurospora crassa serves as a model organism. The results can also be transferred to other fungi and in some cases even human cells.“

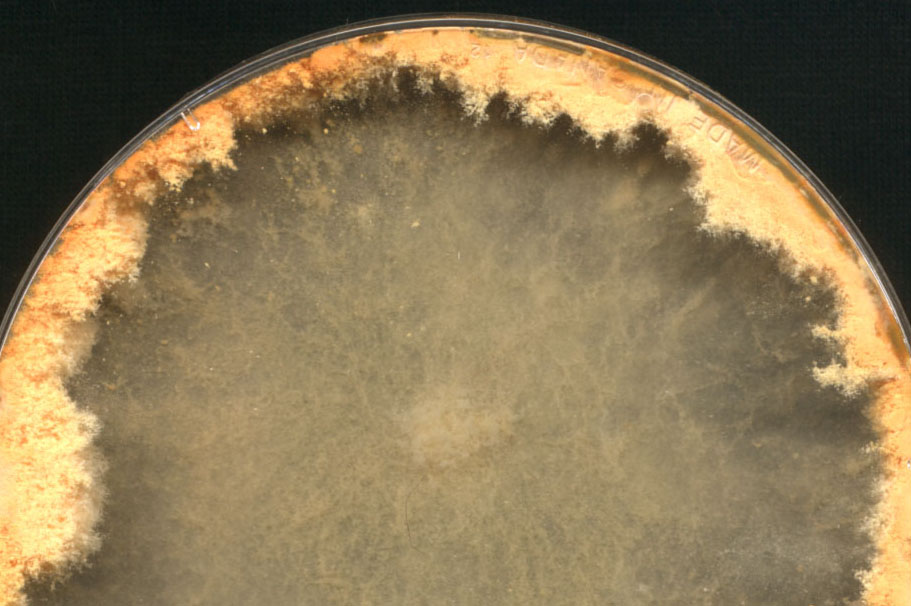

- Laboratory culture of Neurospora crassa. Picture credits: Institute of Genetics/TU Braunschweig

- Electron microscope image. Picture credits: Institute of Genetics/TU Braunschweig

Synergies in research and teaching

The idea for cooperation was born at a conference in Israel. Both professors are researching similar areas and plan to use synergies: Yarden is investigating the molecular basis of the cell growth of fungi, Fleißner is investigating their cell-to-cell communication, cell fusion and differentiation. For the joint project, however, they are not only working together in research but also in teaching. During their mutual stays, the two researchers will take on teaching duties.

Professor Yarden started in February with a lecture on fungi from the ocean, and how they grow, during a visit to Braunschweig. “Oded’s lecture was also very exciting for me because the topic is not directly in my research area,” says Fleißner.” This way, the students saw that the analytical methods they had learnt during their studies were also used in other countries and for very different topics in fungal genetics.” Fleißner adds that the exchange also helps to break through thought patterns and to take on new perspectives.

Building bridges

International exchange in teaching has several other advantages, as Professor Yarden explains: “The students benefit from diversity. The teacher comes from a different country, speaks with a different accent and has a different way of communicating. Science builds bridges and shows that enthusiasm for what we do brings us together.”

For the scientific staff involved in the project, Lucas Well from the Institute of Genetics and Inbal Herold from the Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, this also means travelling: The researchers are planning to spend three to six months in the other country. The next visit is scheduled for autumn: Lucas Well will travel to Israel.