From Podcast to Kapselwurf On Translation Cultures in the Early Modern Era and Today

Abused cod fillet, Spanish fool’s cream, Swedish herring file, or even beaten vegetables. Who hasn’t smirked or shaken their head at unfortunate translations of menus? But how do such translation flubs happen in the first place? When is a translation considered unsuccessful? And what is a translation anyway? That’s what we wanted to know from the Germanists Professor Regina Toepfer, Jennifer Hagedorn and Annkathrin Koppers, who are conducting research in the DFG Priority Program 2130 “Early Modern Translation Cultures (1450-1800)” and who give an insight into their project in the new podcast “Kapselwurf” (Capsule Throw).

Professor Regina Toepfer, Jennifer Hagedorn and Annkathirn Koppers. Picture credit: Institute for German Studies/TU Braunschweig

“Translations have always been done, even in ancient times,” says Professor Regina Toepfer from the Department of Linguistics and Medieval Studies at the Institute for German. For example, from around 250 B.C., the Bible was translated into the ancient Greek language of everyday life. According to legend, this was done by 70 scholars in 70 days. German literary history is also a history of translations, as well, starting with the translation of the Bible from Latin. Yet there are translations that are so close to the original text that you can’t actually understand them without the original work. “In this case, they are more like indexing aids,” Professor Toepfer explains. “Vocabulary aids or grammatical aids that were written over the lines in the Old High German period.” The counterpart to these are texts that translators have rendered very freely, so that they are more like reworks or new works.

In the early modern period (1450-1800), the era to which the scholars of the priority program are devoted, the number of translations increases sharply. The decisive factors here are the educational movement of humanism and the desire to be able to read originals. Especially with regard to antiquity, which is considered the ideal at the time, large bodies of knowledge are being systematically opened up, reports Professor Toepfer. “The early modern period is not as strong in our consciousness as, for example, antiquity, the Middle Ages or modernity. However, many changes happen in this era that are still of formative importance to us today, including in the field of translations.”

From Celtology to History of Science

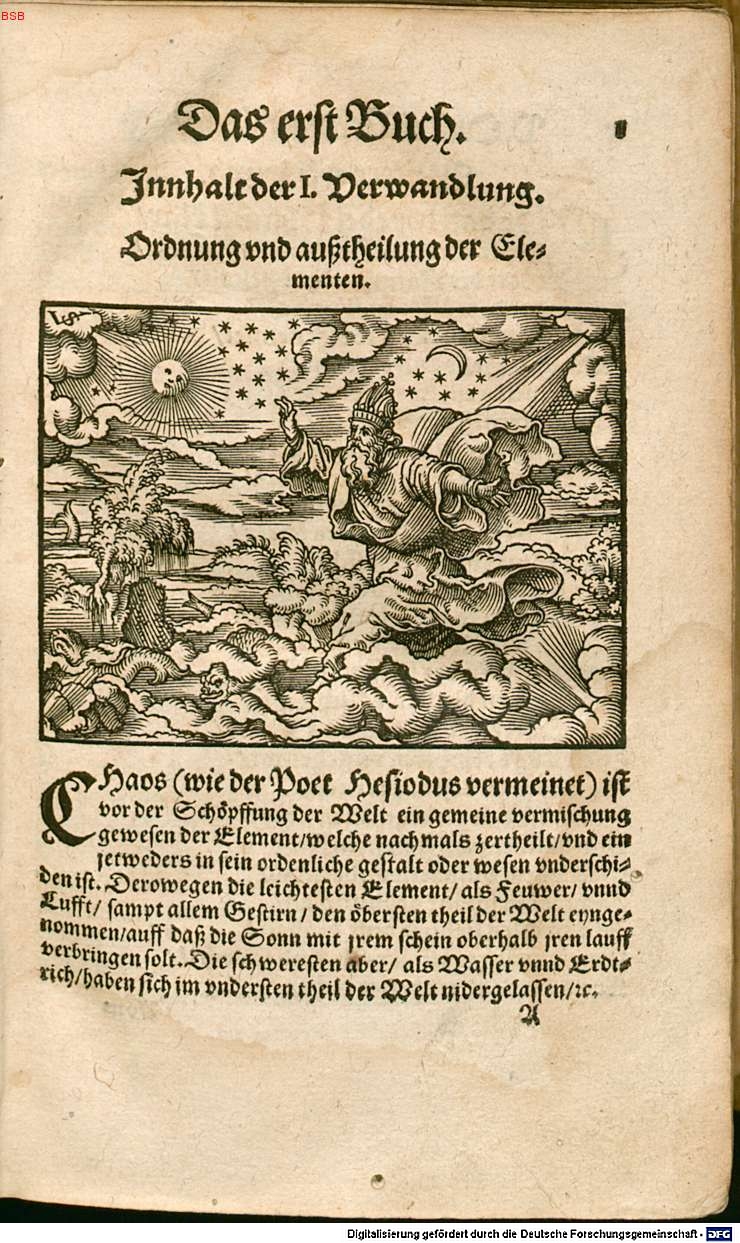

Spreng’s translation of Ovid’s “Metamorphoses”: Ovidius Naso, Publius / Spreng, Johannes / Solis, Virgil: P. Ouidij Nasonis, deß Sinnreichen vnd hochverstendigen Poeten, Metamorphoses oder Verwandlung, Franckfurt, 1564. [VD16 S 8377] .Picture credit: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München, Res./A. lat.a.1240. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.de

How important translation is for social coexistence, communication, scientific progress or relations of action is also shown by current political debates, for example about how to deal with refugees or the development of effective strategies against a pandemic.

A total of 35 scientists are involved with 17 individual projects from the disciplines of Celtic Studies, History, Ancient and Modern German Studies, Romance Studies, Jewish Studies, History of Religion and Art as well as History of Science, spread over 14 locations throughout Germany. For example, some scientists are dealing with the transmission of music or with melody translations. Others are researching maps and their translation or art translations, i.e. how images and architecture are transferred from one culture to another.

Translations of identity concepts

To this end, the researchers involved in the program have developed a multilevel definition of the concept of translation, which Professor Regina Toepfer describes as follows: “We start at the level of the text, with the language, then look at how forms of knowledge, images of humanity and gender concepts change during translation, and finally consider the entire cultural context.”

In their translation anthropology project, “The German Homer and Ovid Translations of the 16th Century from the Perspective of Intersectionality Research,” Professor Regina Toepfer and Jennifer Hagedorn bring together different research directions to answer the question of how images of humanity, concepts of identity, and social power relations are translated from one culture or time to another. In this case, from antiquity to the early modern period.

When a sorceress becomes lust

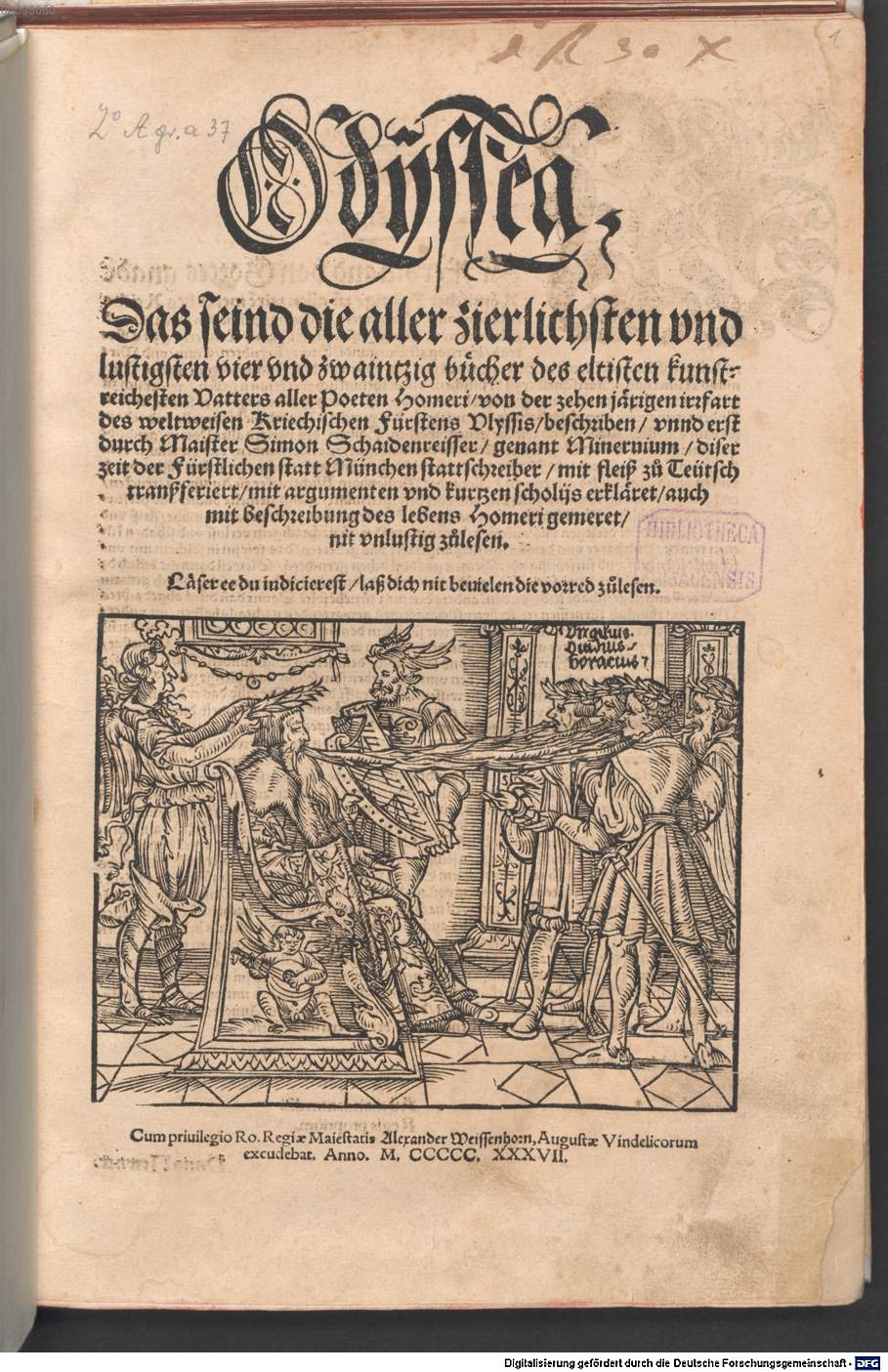

Homerus / Schaidenreisser, Simon: Odyssea, Das seind die aller zierlichsten vnd lustigsten vier vnd zwaintzig bücher des eltisten kunstreichesten Vatters aller Poeten, Homeri, von der zehen jährigen irrfart … Ulyssis, Augustae Vindelicorum, 1537 [VD16 H 4708] .

Picture credits: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München, Res/2 A.gr.a. 37, Titelblatt. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.de

Behind translational anthropology is the idea of recognizing translations as key texts that people have made for people and that therefore reveal a lot about the time in which they were made. “Translators have a power. They shape, they form, they have their own position, body, gender that play into the translation,” says Regina Toepfer. There is no translation that is universally valid, she said. Even if some translations strongly shape our perception, such as the German Schlegel-Tieck translation of Shakespeare.

AI as a work aid

So when is a translation considered a success? “The target audience decides whether the translation works,” says Jennifer Hagedorn. “The specifics of the source text must not be distorted. Translators must take cultural differences into account and respond to them adequately. At the end of the day, there is no general formula for good translation. It is always context-bound.”

This is also the crux of translation software, which is usually the cause of translation flubs on menus. The important creative transfer effort of the translator, who is familiar with the culture of the respective country, is missing. Annkathrin Koppers therefore sees translation software primarily as a work aid: “Even if translation software manages to translate idioms accurately, the transfer from one culture to the other is crucial. Only a person from the culture for which the translation is intended can discover the pitfalls.”

These pitfalls are also explored by four young researchers from the Priority Program in their podcast “Kapselwurf”. Among other things, they want to clarify why the term “Kapselwurf” is not an adequate translation for “podcast” and what might have “gone wrong” during the transfer. The interdisciplinary team forms a so-called TransUnit in SPP 2130, a junior research group that realizes a joint project in addition to networking and exchange. In addition to the TransUnit “Kapselwurf”, four other working groups have come together: “Mission in Translation – Mission (Im)possible?” on missionary translation and catechisms, “Splendid Isolation?”, which sheds light on Brexit on a historical and current level, and “Mapping Translation”, from which a digital map of the translation phenomena under investigation is to emerge.

Dreaming Grass

“With our podcast, we want to illustrate to a broad audience the challenges, difficulties and problems that can arise in translation,” says Jennifer Hagedorn. The four young scientists recorded and edited the pilot episode in their respective home offices. Listeners will learn why it makes sense to give characters different names in some Harry Potter translations, what Chinglish is, and how a sign reading “Do not disturb, tiny grass is dreaming,” meant to keep passersby from stepping on a lawn, rose to minor Internet fame.

More episodes are planned throughout the coming year. In the second podcast episode, the team looks at translation politics. What power relations can translations reflect? And what are political choices in and around translation processes?