Covid-19: Tracking Down the Blueprint for Antibodies Insights into the work of the Corona Antibody Team

Kai-Thomas Schneider and Nora Langreder are PhD students at the Institute for Biochemistry, Biotechnology and Bioinformatics at the Technische Universität Braunschweig. They have been working in the Corona Antibody Team (CORAT) for several months. The consortium develops neutralizing antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In the interview they told us about the search for antibodies at Carolo-Wilhelmina, what antibody libraries are and why teamwork is so important for their research.

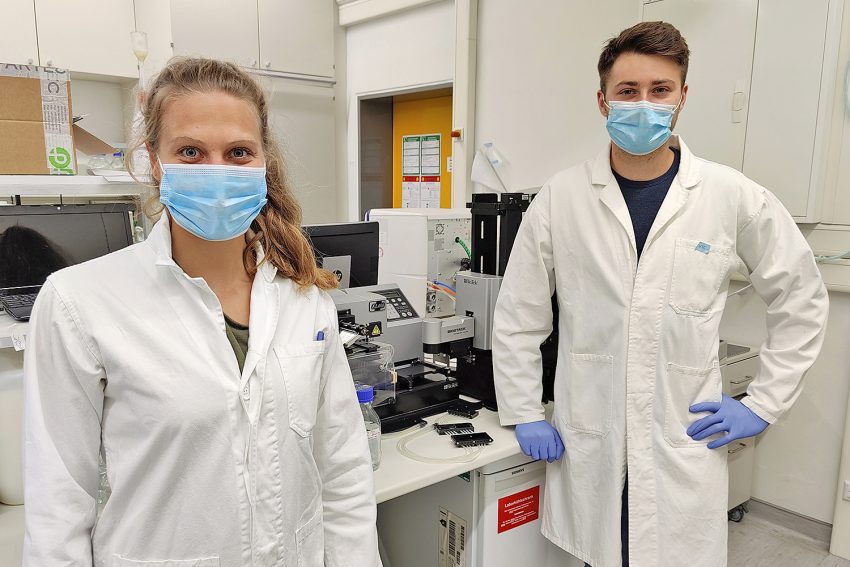

The two PhD students Nora Langreder and Kai-Thomas Schneider work on the CORAT consortium. Picture credits: Michael Hust/TU Braunschweig

Kai-Thomas Schneider and Nora Langreder arrived in a good mood and with mouth and nose protection for our conversation via video conference. They are part of the CORAT consortium that is developing a passive immunotherapy against the corona virus. The two have been pursuing their doctorate at the Institute for Biochemistry, Biotechnology and Bioinformatics for about a year. To support the CORAT consortium they have temporarily put their own projects on hold.

They enjoy working in the consortium, and it shows: “We are happy to be able to make a contribution to helping in the current situation,” says Nora Langreder, and Kai-Thomas Schneider adds: “This includes working on weekends or holidays. But we know what we are doing it for and what can come out of it. That is our motivation.”

How antibodies can help

Antibodies play an important role in the fight against the corona virus: they prevent the virus from entering our cells. When we are ill, our immune system forms antibodies against the pathogens (antigens). Their blueprint is anchored in the immunological memory. If we come into contact with a known antigen again, the immune system can react stronger and faster than at first contact. However, since SARS-CoV-2 is a novel virus, many people have not yet developed antibodies against it.

Passive immunotherapy, which is also being researched by the CORAT consortium, could help here: the administered antibodies could block the pathogen and thus provide protection until the immune system has produced its own antibodies. This way, people who are already ill could be cured and even risk patients or medical staff could be protected. Similar therapies already exist for other diseases such as diphtheria or tetanus. The consortium scientists are confident that they will also be able to find a suitable candidate against the corona virus. But what is the best way to look for it?

Tracking down the blueprint of antibodies

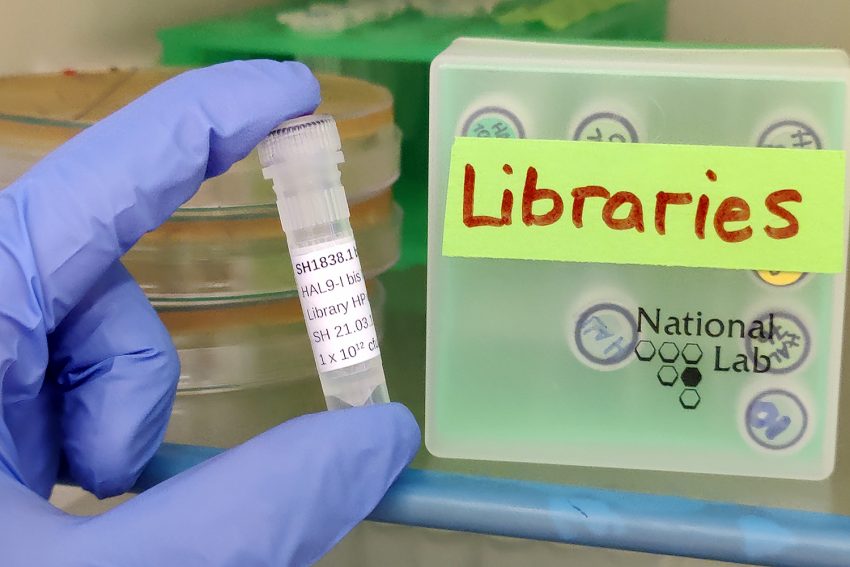

So-called antibody gene libraries contribute to this. They are obtained from immune cells in human blood and stored in small test tubes that can hold about 1.5 millilitres. A gene library of this kind comprises around 10 billion antibody blueprints. “At the institute we have numerous of these antibody gene libraries. They were obtained from human blood in pre-Corona times and, put simply, contain the information for the basic construction of practically all antibodies that the human species can produce,” explains Kai-Thomas Schneider. “These blueprints show the typical sequence of amino acids that determine how particular antibodies look. With this information, we can produce them again and again.”

This small tube contains an antibody library with about 10 billion antibody blueprints. Picture credits: Michael Hust/TU Braunschweig

In addition, the team has also created such libraries from the blood of cured corona patients because the probability of finding a suitable antibody is even greater in such cases. Using the antibody gene libraries, the team is now testing which antibodies bind to the protein envelope of the corona virus and thus prevent it from intruding into other cells. They then test for inhibition, i.e. whether the antibody is able to inhibit the corona virus from docking to the cells. “At first we don’t test with the real corona virus, but only with part of the virus’ surface. This part, however, is essential for the viruses to dock to the cell. This is how we make a preliminary selection,” says Nora Langreder. The antibodies with the best characteristics are then passed on to the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI). There, SARS-CoV-2 viruses are used to test whether the antibodies can block these viruses.

Antibodies from the test tube

The antibody gene libraries and the antibodies for the tests are generated by the PhD students together with the rest of the team led by Professor Stefan Dübel and Professor Michael Hust from the Institute of Biochemistry, Biotechnology and Bioinformatics using the antibody phage display. “This is a method of producing antibodies in the test tube without the immunisation of animals,” explains Stefan Dübel, one of the inventors of the method. “Human monoclonal antibodies, i.e. antibodies from a single cell clone of human blood, are attached to the surface of a phage, a kind of ‘transport virus’. Antibodies produced by this method have the advantage that they are not synthetic or chemically produced substances, but are the body’s own molecules and therefore have hardly any side effects.

“A doctoral thesis on a larger scale and in less time”

In order to find suitable antibody candidates against the corona virus, the team at Carolo-Wilhelmina is working at full speed. “Before Corona, each of us did our own research on his or her own project. The work now feels like a doctoral thesis on a much larger scale and in less time, which we are all doing together as a team. It works great because we can rely on each other,” says Nora Langreder describing the collaboration. Kai-Thomas Schneider adds: “We have all learned a lot and have grown together as a team. The work in the laboratory only works because everyone helps. Even supposedly minor tasks such as ordering materials or sterilizing work equipment are important for research to function. We are particularly grateful that the technical staff here also provides us with fantastic support.

What’s next?

In cooperation with the biotechnology company YUMAB, a spin-off of the TU Braunschweig, the Carolo-Wilhelmina researchers have investigated several thousand antibodies. 47 of the best inhibiting antibodies were handed over to the HZI for further testing. Here, more than twenty antibody candidates have already been identified which neutralise the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus. “Finding such neutralizing antibody candidates was our most important milestone on the way to a passive immunotherapy against Covid-19, but there are still many more steps and tests to be done before the final drug is ready for use,” says Michael Hust. Normally, the corresponding approval procedure takes about one and a half years or more. In cooperation with partners from research institutes, university hospitals and companies, the team is looking for ways and means to shorten these processes and still comply with all necessary safety and quality requirements for drugs. “The next step will be clinical trials, which hopefully can start in autumn,” says Stefan Dübel. Only after successful clinical trials can the drug reach hospitals and doctors’ practices.