Still on the trail of the mercury secret Dr. Marta Pérez Rodríguez on her Fram Strait expedition

At the beginning of June, Dr. Marta Pérez Rodríguez from the Institute of Geoecology at Technische Universität Braunschweig set course for Molloy Deep. On board the research vessel “Polarstern”, she headed for the Fram Strait, the sea area between Spitsbergen and Greenland. During the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) expedition to the so-called “Hausgarten”, the environmental scientist collected sediments from this Arctic region for her studies on the mercury cycle.

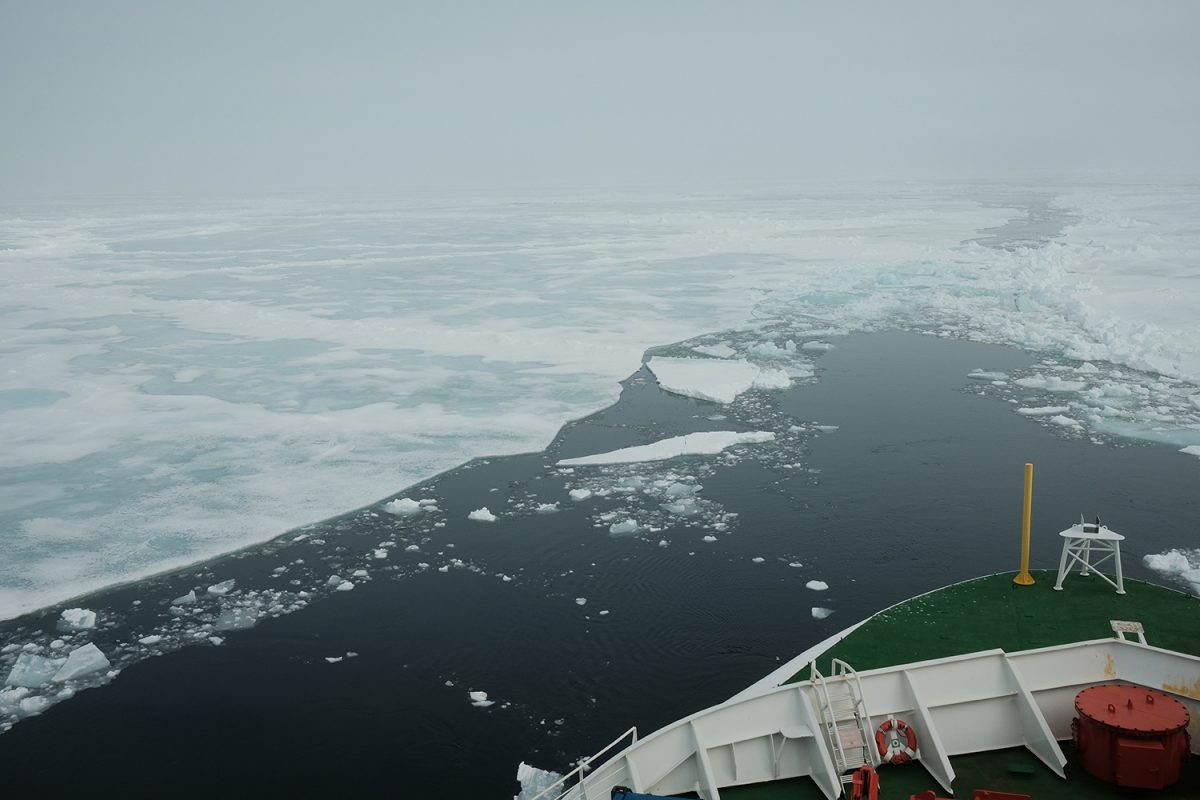

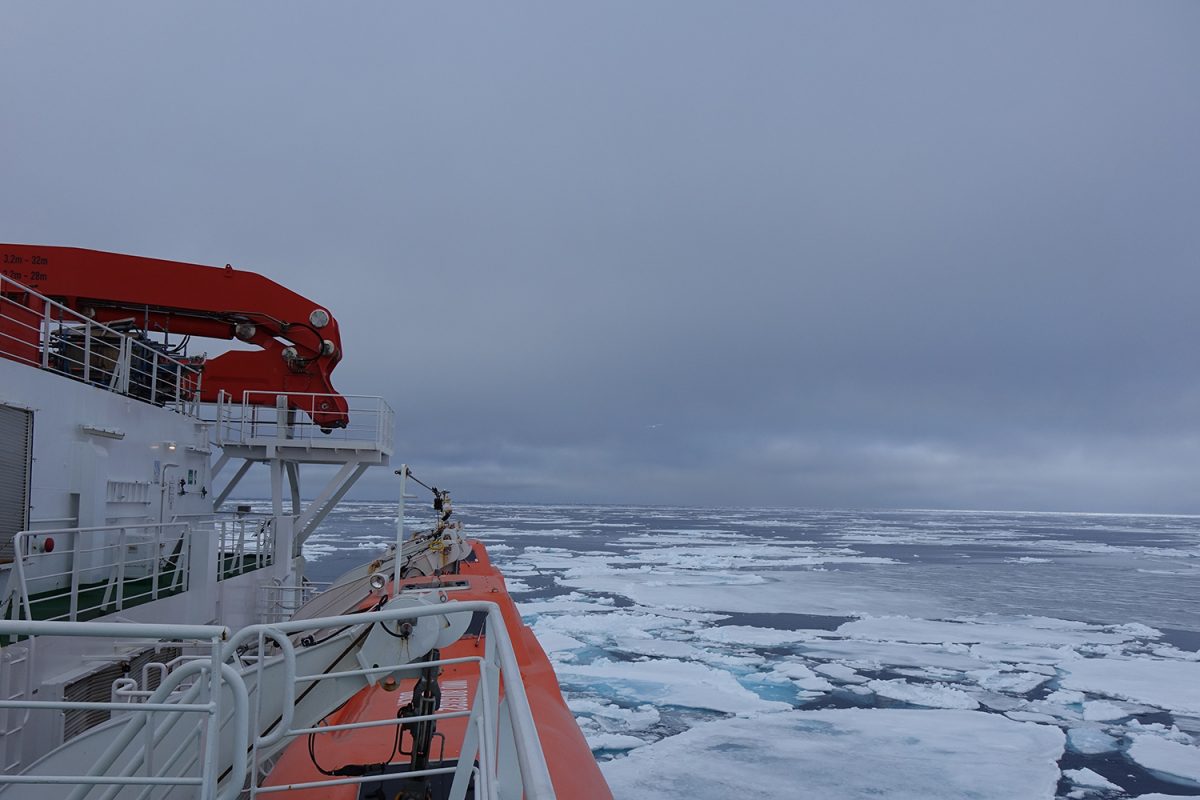

For Dr. Marta Pérez Rodriguez, working among the ice floes was a stark contrast to her previous expedition on the “Polarstern”, where she only saw the open sea for 50 days. Photo credit: Dr. Marta Pérez Rodriguez

For Dr. Marta Pérez Rodríguez, “PS143/1 Hausgarten/FRAM 2024” – the name of the expedition led by Dr. Frank Wenzhöfer – was the second research cruise on the “Polarstern”. In October 2022, she had already sailed with the AWI icebreaker to collect water and sediment samples in the Antarctic waters around South Georgia and to find out where mercury is deposited in the depths of the ocean.

So now, the “Hausgarten” – a long-term marine ecology observatory in the Fram Strait between Greenland and Spitsbergen, which is operated by the AWI and celebrates its 25th anniversary this year. Its purpose is to record the effects of large-scale environmental changes on the marine ecosystem in a transition zone between the North Atlantic and the central Arctic Ocean.

Reducing mercury exposure

Pérez Rodríguez focuses on the mercury cycle and primary production in the oceans. Since 2016, Professor Harald Biester and Dr. Marta Pérez Rodríguez have been researching the highly toxic trace metal in the ocean and marine environment, which can severely damage the health of organisms. Most mercury pollution enters the atmosphere through the burning of coal and other fossil fuels, as well as industrial activities, and remains in ecosystems for long periods of time. In the Department of Environmental Geochemistry at the Institute of Geoecology, researchers are investigating what processes take place in different ecosystems, what links exist between them and how environmental changes can alter or intensify these processes. “This knowledge can help to develop better regulations and control systems to reduce the effects of mercury pollution,” says Marta Pérez Rodríguez.

Together with a team from the Danish Centre for Hadal Research at the University of Southern Denmark (Ronnie N. Glud), Marta Pérez Rodríguez was able to collect important samples for her research during the expedition and continue previous research work with the Danish scientists. Together they are investigating the processes of formation and accumulation of mercury, methylmercury and other metals in the deep sea. The focus of her research is therefore the hadal zone, the deepest part of the seafloor at more than 6,000 metres. For the environmental scientist, it was crucial that the expedition also included sampling in the Molloy Deep. Although this part of the Arctic Ocean is only 5,500 metres deep and therefore does not meet the definition of the Hadal Zone, it has Hadal characteristics according to the data collected so far.

Best weather conditions for research

The weather conditions were ideal for the research – in contrast to the Braunschweig scientist’s first expedition to the South Atlantic in 2022, where waves were up to twelve metres high in places. “This time we were lucky. The waves were minimal for most of the expedition, so it almost felt like we were at sea,” says Marta Pérez Rodríguez. “This allowed us to carry out all the sampling without any problems.”

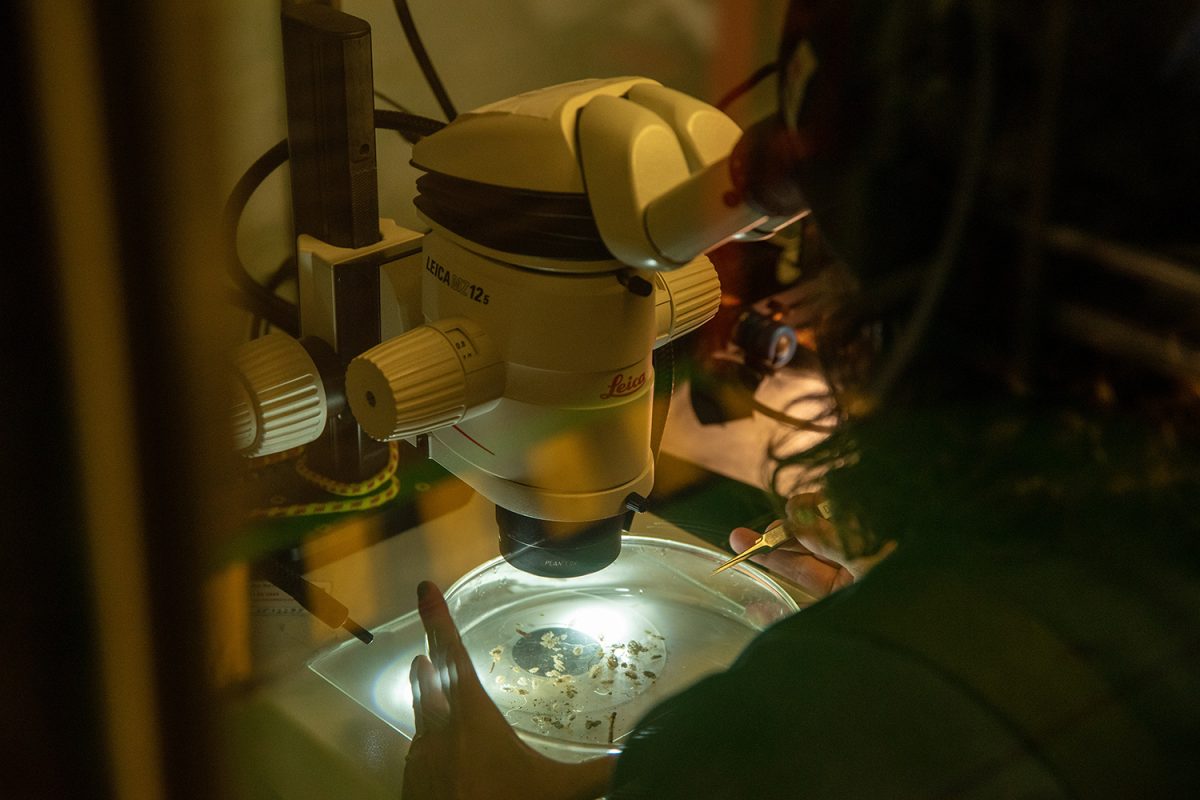

For her work in the Environmental Geochemistry Working Group, she collected surface sediment cores along a section between Svalbard and East Greenland, which serves as a transect for primary production. She also collected two longer sediment cores (30 centimetres each) from the Molloy Deep and a reference zone. “We want to use these samples to understand how primary production in the surface water affects the accumulation of mercury in the sediments through a process known as ‘scavenging’. This is the transport of mercury from the water column by sinking particles of organic matter,” explains Marta Pérez Rodríguez. To this end, she and Dr. Peter Stief from the Danish Center for Hadal Research at the University of Southern Denmark have set up a laboratory experiment using pressure tanks to simulate conditions at depths of 6,000 metres and more, and to observe the effects on mercury and methylmercury concentrations in sinking particles.

The tanks simulate the enormous pressure exerted on the particles as they sink through the water column into the deep sea. “This is quite unique. The tank allows us to simulate the extreme pressure conditions that prevail in the deepest parts of the ocean – up to 100 megapascals – and to observe how the particles change during a ten-kilometre descent,” says Marta Pérez Rodríguez.

Dr. Marta Pérez Rodriguez (l.) cutting the sediment cores. Photo credit: Yen-Ting Chen/University of Southern Denmark

Live videos from the seabed

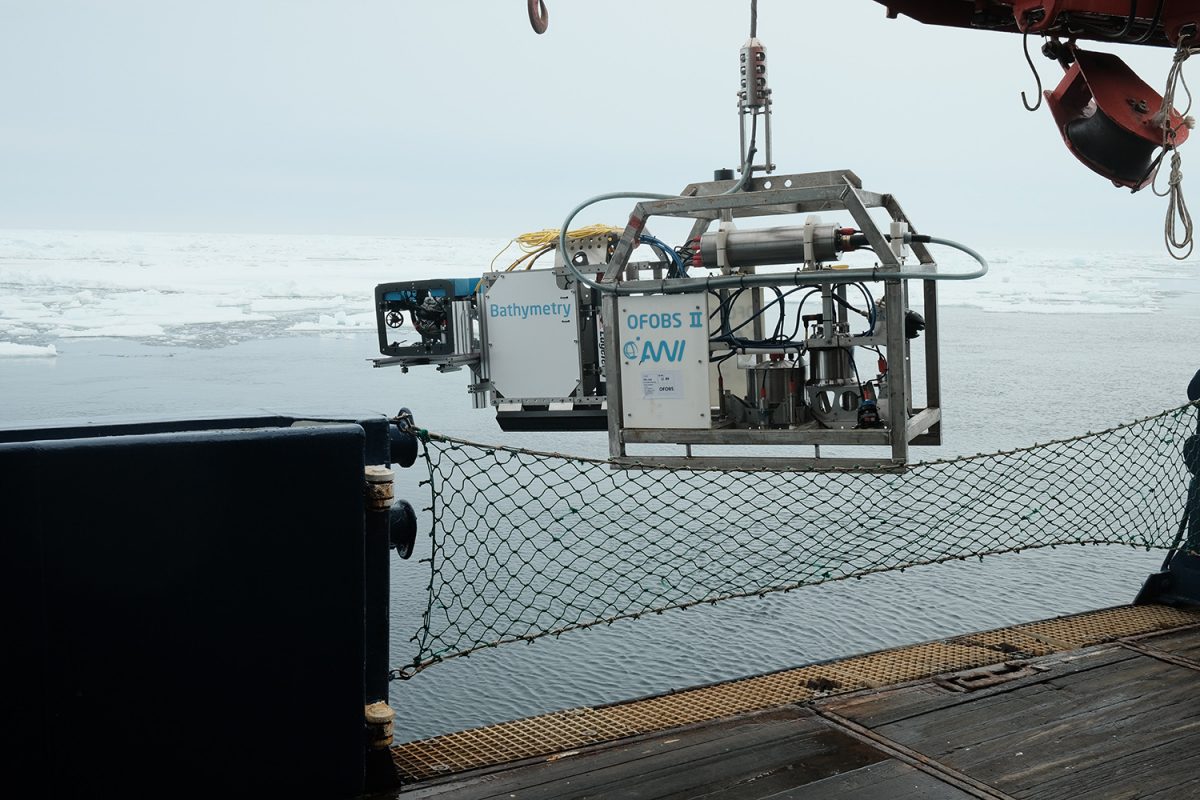

The approximately 50 researchers on board used a wide range of innovative instruments for their investigations. For example, the “OFOBS” (Ocean Floor Observation and Bathymetry System), which was developed by the AWI deep-sea group. This instrument is towed at low speed close to the seabed and records images and live videos of the seabed, which are sent back to the ship. This allows everyone on board to observe what is happening in the Molloy Deep at a depth of more than 5,000 metres.

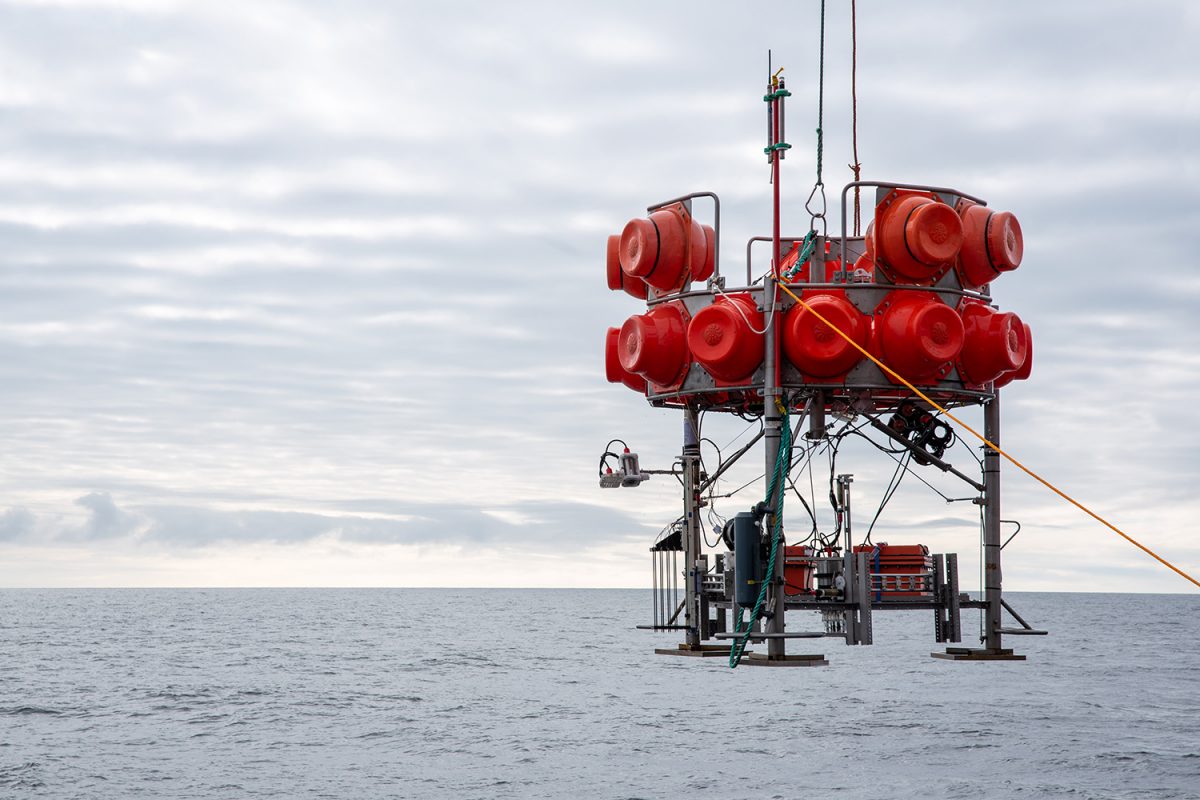

Several so-called landers have also been deployed. These instruments are lowered to the seabed where they remain for a period of time – usually around 24 hours – to take various measurements and records. The data are also used for geochemical interpretation of the mercury and methylmercury data collected by the Braunschweig scientist.

The MUC (Multicorer), a marine geological research instrument, was used for Marta Pérez Rodríguez’s sampling. The MUC is sent to the seabed and collects sediment samples in tubes. When it returns to the surface, the sediment is removed and cut open to create a vertical and intact record of the seabed sediments. “What was new for me this time was that the MUC was equipped with a camera that transmitted images to the ship in real time, so we could see exactly where the cores were taken,” says the scientist.

Back in Braunschweig, she is looking forward to analysing the samples and evaluating the results. “This research will provide valuable insights into what happens to mercury and methylmercury when algal particles sink and will improve our understanding of these processes in the deep ocean.”

“Hausgarten“

25 years ago, the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, established a long-term marine ecology observatory in the Fram Strait between Greenland and Svalbard. Its purpose is to record and monitor the effects of current large-scale environmental changes on the marine ecosystem in a transition zone between the North Atlantic and the central Arctic Ocean. While individual nations plant their national flags on the deep-sea floor to assert their territorial claims, the AWI researchers, with self-deprecating intent, have placed a garden gnome in their “Hausgarten“ (home garden).