More Effectiveness, Fewer Side Effects On the way to individualised medicine

Politicians and researchers see individualised medicine as an essential building block for the health system of the future. It is about effectiveness, but also about efficiency, new technologies and data protection. How far have we come with this? What are scientists at TU Braunschweig researching? We talked about this with Professor Arno Kwade, who has just been awarded the Lower Saxony Science Prize for his research in the field of particle technology and its importance for medicine, and Dr Jan Henrik Finke, who, as a pharmacist with a doctorate, heads the pharmaceutical and bioparticle technology department at Professor Kwade’s Institute for Particle Technology.

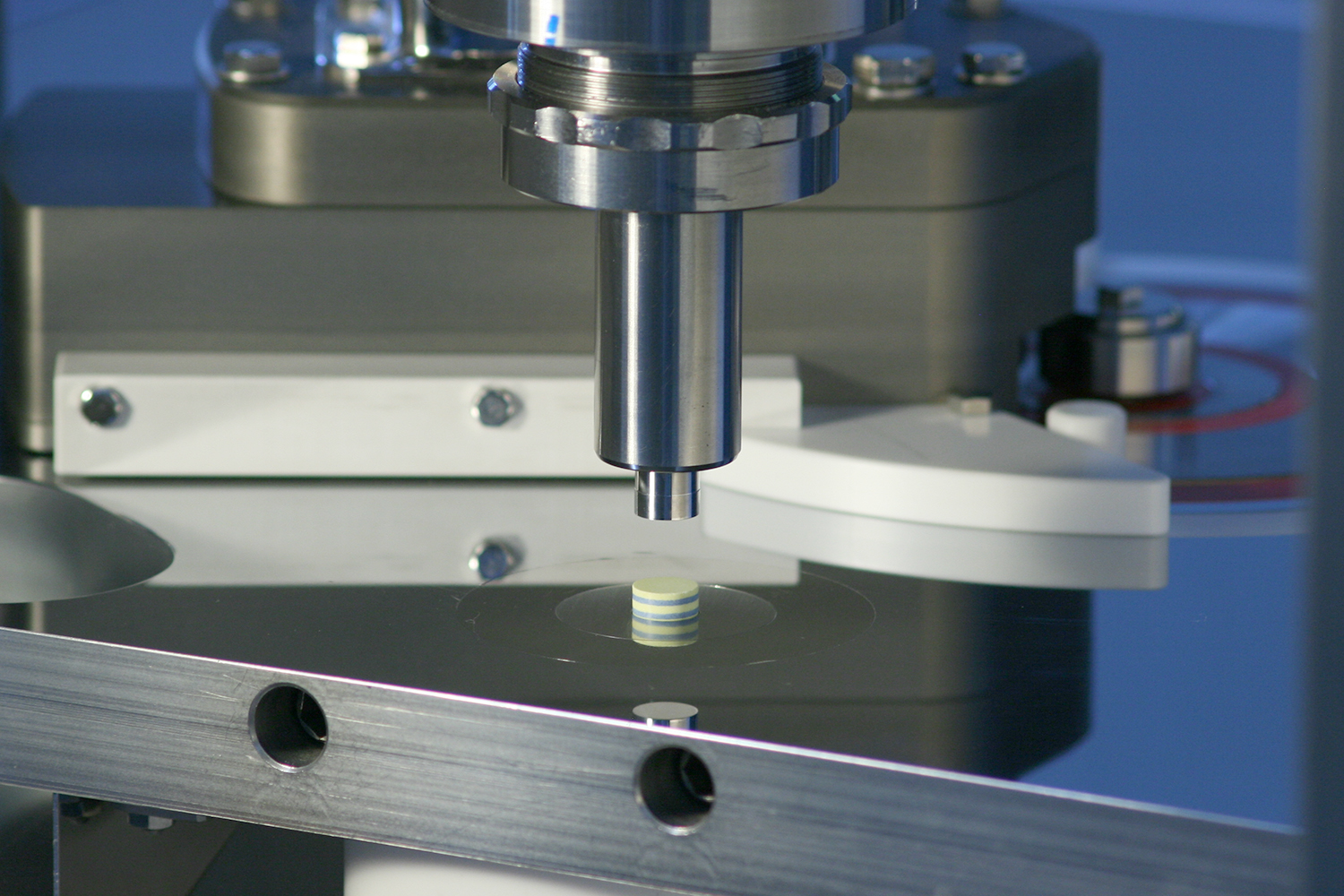

For example, multi-layer tableting allows dosage forms to be tailored to the individual needs of patients. Here, different drugs can be safely combined in one dosage form, doses of active ingredients can be effectively adjusted, and release behavior can be controlled. In addition, by using the compacting simulator shown here, important information for quality control and research can be collected safely online. Photo credits: Jan Henrik Finke/TU Braunschweig

The Federal Government has put the topic on the agenda under the umbrella term of personalised medicine in its framework programme for health research: “The goal of systems medicine is (…) not only to better understand disease mechanisms, but also to derive individual prevention and treatment options from them – as a precursor to personalised medicine”. This is based on the individual lifestyles and needs of people, but also on the knowledge that every disease is dependent on many processes and influencing factors that vary from organism to organism. Accordingly, for example, a certain drug or a certain therapy for the treatment of a disease is not always the best solution for all people suffering from the same disease. It is also not always clear how effective a therapy is and what side effects and interactions can occur. The prospect of greater efficiency in the healthcare system, more safety and a better quality of life for patients make research into new treatment approaches relevant.

Catering to individual patients

“We tend to speak of individualised medicine here, as it really pursues therapies tailored to a single person, whereas personalised medicine addresses therapies for groups of patients (with common characteristics),” Professor Arno Kwade specifies.

In order to make this therapy decision, factors such as gender, previous illnesses, interactions with other medicines, intolerances, genetic characteristics, environmental influences are taken into account. “Each patient then receives exactly the therapy and, in particular, the dose and combination of medicines that are needed based on the individual clinical picture and the respective constitution at each point in time,” says Dr. Jan Henrik Finke. The therapy is thus centred on the patient. This is also associated with a patient-friendly intake of medicines. “In this way, they follow the therapy more faithfully and thus receive the best individual health outcome.”

However, individualised medicine is not only about treating diseases. The aim is also to find out whether the organism has a predisposition to certain diseases. If this is known, the risk of disease can be reduced or delayed in time. In short: Individualised medicine should help to better understand, predict, treat and prevent diseases in individuals.

For which diseases could the use of individualised medicine play an important role?

“For example, in cardiovascular diseases such as high blood pressure, but also in cancer. Basically, wherever we usually have to work with a combination of active substances and where the doses have to be adjusted to the constitution and hereditary disposition of the patients,” says Dr Finke.

In cancer therapy, the selection of active substances, their dose and their administration are already put together individually for each patient today.

Adaptation of drug production

In order for this patient-specific approach to succeed, researchers at the Centre of Pharmaceutical Engineering (PVZ) at TU Braunschweig are working on miniaturised active ingredient and drug production facilities. This is because individualised therapy requires completely new concepts for manufacturing facilities, as it is not possible to meet this challenge with facilities tailored to industrial mass production. For this purpose, high-precision and also highly flexible facilities have to be newly developed. Professor Kwade describes the practical supply as follows: “The doctor prescribes the patient a selection of active substances and their dose. The data for this are transmitted digitally to the respective pharmacy, which uses special machines – for example 3D printers for tablets or capsule filling machines – to produce the individualised medicines in the desired quantity. Ideally, these are then integrated into an intelligent packaging device that ensures the doses are taken safely at the right times.”

Challenges in research

The paradigm shift in patient care poses major challenges for research. For the use of individualised medicine, it must be possible to produce small quantities of drugs economically. It must be ensured that the dosage of the right active ingredients and excipients is precise, safe and traceable. Interactions between active ingredients are of particular importance. If these are known, newly discovered active ingredients can also be integrated directly. In contrast to mass production, random samples of a production batch cannot be examined destructively for their quality – this is uneconomical for quantities close to 1.

“Instead, the need must be addressed to establish new, non-destructive analytical methods, including their digital evaluation algorithms, to ensure the safety of the individual medicines produced,” says Dr Finke.

TU Braunschweig is also conducting research in many other areas – together with university partners and the two Fraunhofer Institutes for Surface Engineering and Thin Films (IST) and for Toxicology and Experimental Medicine (ITEM), together in the Fraunhofer Performance Centre for Medicine and Pharmaceutical Technology, as well as the pharmacy association Auriga.

In pharmacology at TU Braunschweig, for example, the effect of combinations of active substances is described and in pharmaceutical technology and biopharmacy intermediate products (intermediates) with active substances and excipients are developed. At the Institute of Machine Tools and Production Technology (IWF), scientists are working on apparatus and automation concepts for manufacturing and mapping manufacturing as a digital twin. A digital twin predicts the product properties based on the production history of the individual medicinal product and can thus be used in future for quality assurance as well as for process control.

Data and economic efficiency as a basis

The basis for individualised medicine is data, for example information on health status and lifestyle (diet, sport, smoking, alcohol). New diagnostic procedures and treatment methods can be derived from this data. A tailor-made treatment strategy could then be offered before therapy begins.

According to Professor Kwade, it is important here that the security of personal data has top priority. The economic side is also of enormous importance in research into individualised medicine: on the one hand, with regard to the production of individualised medicines, which has a high degree of automation – comparable to the handling of a coffee machine; on the other hand, a wide variety of stakeholders must be involved in the development process at an early stage, so that patients, doctors, pharmacists, drug manufacturers, but also the payers (health insurance companies) are open to financing the innovative therapies.