Cultural heritage as a resource Professor Elisabeth Endres on the joint exhibition with the State Office for Monument Preservation

What can we learn from cultural heritage for building in the future? What potential for climate protection is there in architectural monuments? And what new demands on the building industry result from this? These are the questions addressed by the project “Ressource Kulturerbe” (“Resource Cultural Heritage”) of the Lower Saxony Landesamt für Denkmalpflege (Lower Saxony State Office for Monument Preservation) and the Institute for Building Climatology and Energy of Architecture (IBEA) at Technische Universität Braunschweig. On the occasion of the exhibition, IBEA director Professor Elisabeth Endres reports on why existing buildings should be given top priority among architects and in teaching.

Professor Elisabeth Endres: “Our comfort requirements are too high.” Photo credit: Markus Hörster/TU Braunschweig

Professor Endres, do monument protection and climate protection go together?

The aim of the exhibition “Ressource Kulturerbe” is also to show that these two aspects do not have to be contradictory. The monuments date from a time when different demands were placed on buildings, especially in terms of comfort. Many of our problems today are caused by this. What we can learn from the monuments is how simply people used to build and get by.

Another aspect of why cultural heritage offers great potential for climate protection is the “grey energies” contained in the materials and constructions. That is why we have also included the thesis “Klug bilanzieren statt stumpf Rechnen” (“Balancing cleverly instead of calculating mindlessly”) in the exhibition. It is not only about the operation of a building, but also about its longevity and the energy that was used to construct it.

What can we transfer from traditional knowledge into the future?

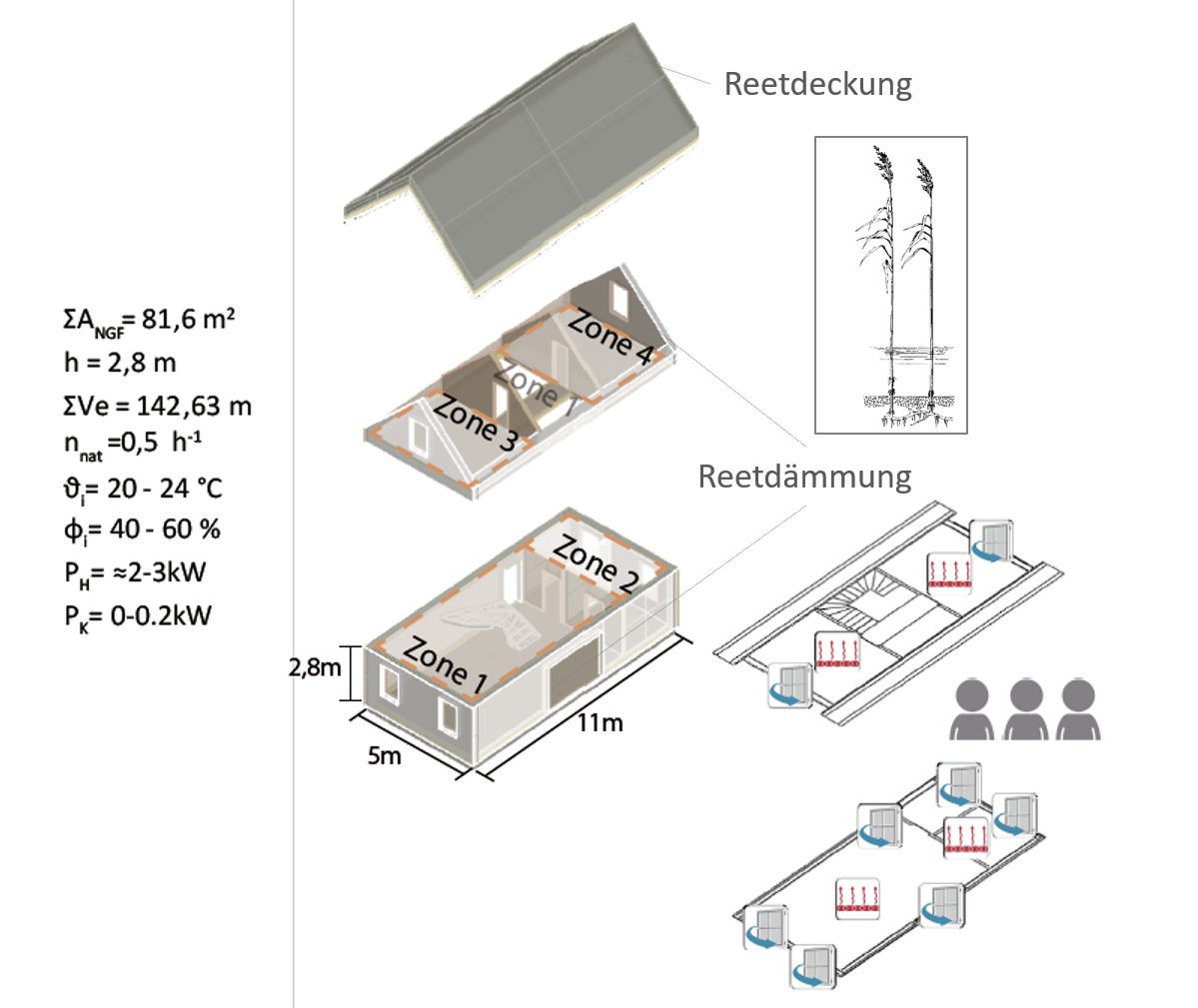

For example, the ability to repair. In the “Reet reloaded” project with Professor Almut Grüntuch-Ernst’s Institute of Design and Architectural Strategies, we are looking at just that. In the past, the lack of components allowed for single-variety building. It is a great advantage to have this knowledge through the monuments: how simple and repairable connections can be, how durable main components are and how they can be replaced when they are weathered, for example, like façade protection areas or roof coverings.

It is also important to think regionally again and to preserve regional building materials and traditions. To this end, we have formulated another thesis in the exhibition: “Zurück zum Ort: Tradition als Potential” (“Back to local places: tradition as potential”). A simple and catchy example: flat-pitched roofs are more likely to be found in snowy areas; in regions with a lot of rain we still see very steep roofs today. We can learn from these local building methods in order to build more simply and in a more climate-resilient way.

In the “Reet reloaded” project, architecture students look at thatched roofs on Sylt and also measure them with regard to their performance in terms of building physics. Picture credits: IBEA/TU Braunschweig

Are our demands on buildings today too high?

One major factor is our comfort requirements, which are too high. Currently we are forced – also at our university – to cope with lower temperatures in offices and living spaces, and even if it is brutal, it will make a difference, I hope. For example, does every room in a building – whether used or not – have to have the same temperature? That you can move around in every room without having to change anything and that the building serves me and gives me energy so that I feel comfortable to the maximum is, in my opinion, the wrong way of thinking about the demands on buildings. Society needs to rethink this.

Future summers will present us with challenges in the form of increasing periods of heat. If we have the same high demands here, it will be difficult to use the buildings in a simple way – especially the newer building stock with high proportions of glazing.

One question is also whether we should increase the hours of use of buildings. Many buildings are empty in the afternoons and evenings. Maybe they are not maximally ideal for this or that use, but for another.

Keyword: energy efficiency. Are the buildings prepared for the future?

With existing buildings, you always ask yourself why the building has been functioning for so long – also in terms of climate technology? Well, most existing buildings are already well prepared. I’m not against optimising energy efficiency, but the question is how much does it cost us to fight for the last kilowatt hour saved.

Nobody says anything against insulating the top floor ceiling. And: the insulation of storey and basement ceilings is more efficient in terms of building physics compared to some exterior wall insulation, which is applied at great expense as well as changing the appearance. If you build a new roof and insulate it properly, this is no problem, nor is the installation of better windows. With such measures, I can already create a lot of comfort and save energy. Often people exaggerate and run after an efficiency house standard without considering whether the effort is appropriate for the benefit. This also includes questioning the use of technology to save energy, for example central ventilation technology with heat recovery.

In my view, it is important to define a goal in building projects, namely the environmentally compatible operation of the building. This can be achieved through an efficient building, a high degree of sufficiency in handling and/or the use of renewable energies. We need to act urgently in the existing building stock and achieve success on a broad scale, not just achieve maximum efficiency in individual pilot projects.

The buildings are ready, I think, but we are not really. Our planning processes, the Fee Regulations for Architects and Engineers (HOAI), the regulations and standards, all these issues are always geared towards new construction. And we don’t take the time to examine houses properly and also to see the advantages and not just the faults of the house.

What would have to change here?

Our funding landscape needs to change completely. The funding programmes have been carried over from the 1990s. We have to rethink what we actually need today. Likewise, the Gebäudeenergiegesetz (Building Energy Act) should be much more geared to the existing building stock. In principle, renovation should be promoted more than new construction.

In the fee regulations, too, one should work much more with the tried and tested dynamic tools and measurements in order to represent the actual performance and not statically calculate key figures in the existing building stock. This approach never does justice to the buildings. The good thing about the existing building stock is that we can learn much more if we look at it properly. However, this is currently not part of our planning culture.

The building material clay was investigated in the Hagenmarkt real-world laboratory. Photo credit: IBEA/TU Braunschweig

Should these considerations also have an impact on the teaching of architecture?

I recently said somewhat provocatively that students in the Bachelor of Architecture should no longer be allowed to plan new buildings. The proposal was: we teach the Bachelor’s curriculum on the existing building stock and in the Master’s we do the “freestyle” of new construction. Of course, this would be a radical change in architectural education, but integrating the existing building stock and the continuation of existing structures more strongly into the curricula is very desirable and necessary, because the attitude of the architectural profession should also change. Building in the existing stock is not so attractive, perhaps also because it is then not a matter of “first authorship”. When I was a student, architects who worked on existing buildings were considered “second-tier” designers. Not much has changed, but the urgency and need for action is higher than ever and the topic belongs in the front row.

The existing building stock must also be given a completely different standing in the architectural community. We can only achieve this if we also start it in teaching. We should look more at the existing buildings with the students, as the Institute of History and Theory of Architecture and the City (GTAS) has already done in the project on the former Galeria Kaufhof building on Bohlweg here in Braunschweig or in the joint project in the Eifel with Professor Vanessa Miriam Carlow.

And also with “Reet reloaded”, we looked at the roofs on site on Sylt and are currently measuring them with regard to their performance in terms of building physics. There we met and discussed with a roofer who builds thatched roofs. And we also looked at a traditional building material at Hagenmarkt: clay. Exploring this building material is particularly important to me. And not looking backwards!

Progress always has something to do with looking forward, but it can develop from looking back. That’s what I also tell the students: You have to walk through the world with your eyes open.