Building in times of crisis Professor Patrick Schwerdtner on price increases for building materials

For months, prices for building materials went in only one direction: up. Disrupted supply chains, rising energy prices, material shortages as a result of the Covid pandemic and the Ukraine war have also had a significant impact on the construction sector. Reason enough for the Institute for Construction Engineering and Management at TU Braunschweig to tackle the topic under the title “Preis und Lieferrisiken durch höhere Gewalt: präventive und reaktive Lösungen” (Price and supply risks due to force majeure: preventive and reactive solutions) at the 19th Braunschweig Baubetriebsseminar with more than 200 participants. Bianca Loschinsky spoke with Institute Head Professor Patrick Schwerdtner about price developments and forecasts for the coming years.

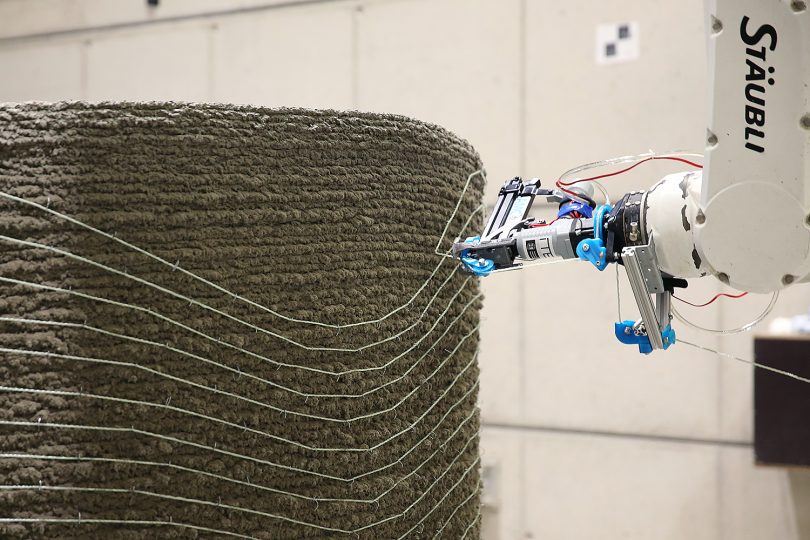

For some building materials, a veritable explosion in costs could be observed. Photo credit: IBB/TU Braunschweig

Mr Schwerdtner, in 2021 and 2022 we could observe a veritable cost explosion for building materials. Do certain building materials stand out in particular?

It is indeed worth taking a differentiated look at the development, as a closer look reveals considerable differences. For example, flat glass, which is usually used for windows, glass doors or walls, is the material with the biggest price increase – almost 50 percent. One reason for this is certainly the very energy-intensive production. But steel bars were also far above the usual level with a price increase of about 40 percent. In contrast, the prices for construction timber rose by only 1.3 percent – a very moderate value after the big jumps in 2021.

For some materials, prices have calmed down in the meantime. What are the forecasts?

Last year we had a total price increase of around 15 per cent. In post-war history, construction price increases have only been higher once before: almost 20 percent in 1970. The forecasts also show a relatively high price increase for this year, about six to eight percent. Next year it will probably be somewhat more moderate at around three percent. The institutes are not looking any further ahead.

Then how do you determine the approaches for long-running projects?

In our own long-term assessments, we refer to various statistical analyses and use them to determine characteristic courses of the past ten to 15 years, taking into account the indices relevant to the project. We also advise various public sector clients in this way and then develop specific recommendations for each project.

So there is little hope for falling prices?

There are currently no signs of a general price decline – with the exception of selected building materials. Only the upward price trend is clearly reducing. We may even see a phase with increases of less than one percent. At the moment, however, I know of no forecasts that assume falling prices for the realisation of buildings in an overall view.

Moreover, I do not expect us to slip back into the calm spheres of ten years ago. The dynamics of raw material prices and availability will continue to accompany us. For one, the constant shortage of individual raw materials, such as sand, which is important for the production of concrete and glass, is leading to growing nervousness on the market. In addition, the geopolitical situation will remain difficult for the foreseeable future and the consequences of climate change cannot yet be estimated.

If certain building materials become more and more expensive, doesn’t the building industry have to change its mindset, for example towards renewable raw materials?

Indeed, we need to rethink. To ensure price stability and guarantee availability, strategic considerations and partnerships to establish alternative supply chains may make sense.

Renewable raw materials are not necessarily cheaper from a monetary perspective, but certainly from an ecological perspective to reduce CO2 emissions. Among other things, we can make greater use of wood for load-bearing constructions, if necessary also in hybrid constructions with conventional building materials. But not all alternatives have been well researched and the installation of recycled material is not yet readily possible everywhere.

It is important that we rethink planning and building, but unfortunately this does not work at the push of a button with just one measure. In addition to using renewable raw materials, we also need to use resources more efficiently and enable reusability. Recycling will not be enough in the long run. But this is a process in which all stakeholders must participate – from the initiation phase to the recovery of the raw materials.

Even before the pandemic and the Ukraine war, the costs of various major projects were rising immensely. What share did the general price development have at that time?

The share depends on the project, of course – and the respective share of other influences such as subsequent changes, delayed decisions, problems with the building ground, etc. What is very untypical at the moment is that the price increases have such a large share in it and practically came from nowhere. Nobody could have known that.

In the future, the public sector in particular would like to better record possible price increases. The public sector used to budget according to what the realisation of the building would cost at the time of the cost planning. Everyone knew that it would cost more in the coming years, but it could not be budgeted for. A rethink is now taking place. After the construction of the Elbe Philharmonic Hall, Hamburg, for example, published a printed matter entitled “Kostenstabiles Bauen” (“Cost Stable Construction”) and spoke out in favour of factoring in increases in construction prices. The new RBBau (“Richtlinien für die Durchführung von Bauaufgaben des Bundes” – Guidelines for the Execution of Federal Construction Tasks) now requires that potential price developments be shown and estimated nationwide. A step in the right direction.

Could it lead to crises being taken into account more in building projects in the future?

We tend to have a bit of disaster amnesia. At the moment, price development is of course a big issue. But already now voices are getting louder that believe in an end of the crisis in view of partly declining material prices. But who dares to make a prediction for several years at the moment, when one is responsible for the results?

How could the risks of possible supply bottlenecks and price increases be regulated in advance?

In long-running projects with fixed-price contracts, construction companies cannot simply pass on unexpectedly sharp price increases to the clients. In the worst case, there is a risk of insolvency, which is detrimental to all parties involved. Remuneration must therefore be made more flexible so that the risks are sensibly shared between the parties.

In concrete terms, price escalator clauses can allow the remuneration to be adjusted to market developments. In this way, clients have to participate in incalculable price increases for building materials, but avoid high risk surcharges when submitting bids, which would have to be paid even without a price increase.

Now, we have been talking about price increases in the material sector, but wages could also rise.

Yes, this is to be expected. Achieved wage settlements and ongoing strikes in other sectors already indicate that this will also affect the construction and real estate industry. The situation is aggravated by the shortage of skilled workers – at all levels. This could lead to collective wage agreements being significantly different than in the past.

Is there any good news?

Absolutely. And there are several things. To lower prices, we need to become more productive in construction to produce the same with fewer people. We also need to use resources more efficiently. This is possible with additive manufacturing, for example, and we are already researching this at TU Braunschweig in the special research area Transregio 277 “Additive Manufacturing in Construction” (AMC).

Furthermore, great efforts are being made to use modular prefabrication to build cheaply, quickly and yet with high quality in the future. For many new buildings, we could thus save on personnel resources, which we can then use for complicated one-offs (for example, building in existing structures). The transformation process in the construction and real estate industry has begun in many areas.