Measuring individual molecules with diamond quantum sensors Interview with Professor Nabeel Aslam

Nabeel Aslam became a junior professor at the Institute of Condensed Matter Physics at TU Braunschweig at the beginning of October 2022. For the last four years, Professor Aslam was researching quantum sensors in diamonds at Harvard University. He is now continuing this research at TU Braunschweig, adding a new facet to the core research area metrology and the Cluster of Excellence QuantumFrontiers. In an interview, Professor Aslam tells us how he uses single atoms in diamonds and what inspired him to become a scientist.

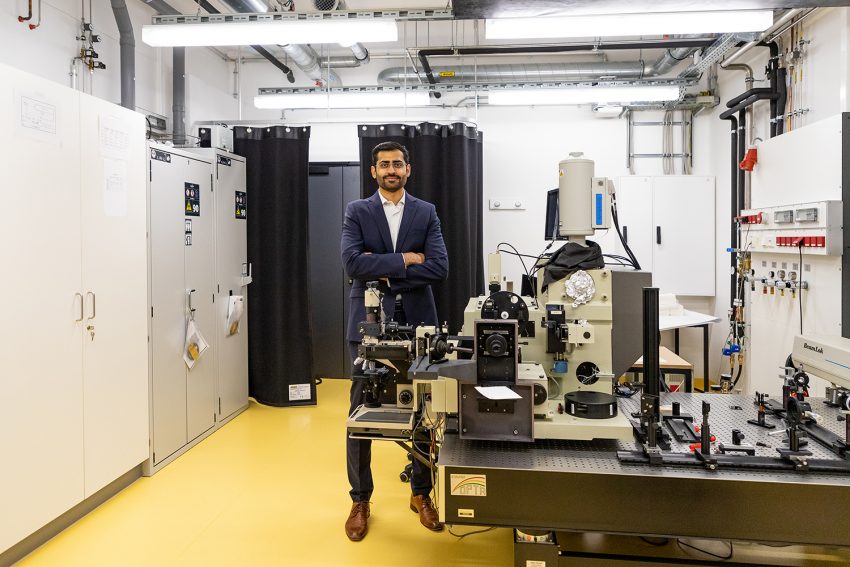

Junior professor Nabeel Aslam at the LENA research centre. Picture credits: Kristina Rottig/TU Braunschweig

Have you arrived well in Braunschweig and at the Carolo-Wilhelmina?

It was definitely a challenge to move back to Germany from the US with my wife and our two children. The call came at very short notice for us, so we only arrived here three days before school started. By now we feel at home and explore Braunschweig and the surrounding area by bike.

I was also warmly welcomed at the university. Right in the first days of my tenure, the annual retreat took place. There I got to know the professors of my faculty and was able to immediately talk about possible collaborations within the university.

Why did you choose the TU Braunschweig?

What excited me about TU Braunschweig were the many activities in the field of quantum technologies and the research focus on metrology. There is a cluster of excellence for quantum research here with QuantumFrontiers and in addition there is the Quantum Valley Lower Saxony. In my research on quantum sensor technology, both aspects – quantum technology and metrology – come together. I fit in perfectly in this area with my focus on quantum sensors in diamonds.

Furthermore, the close connection between the TU Braunschweig and the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) attracted me. As a researcher at LENA, I am directly involved in the jointly operated research centre for nanometrology. Accordingly, I have already identified common interests with PTB colleagues and am looking forward to collaborating with them.

So you are researching quantum sensors in diamonds. Can you explain that in more detail?

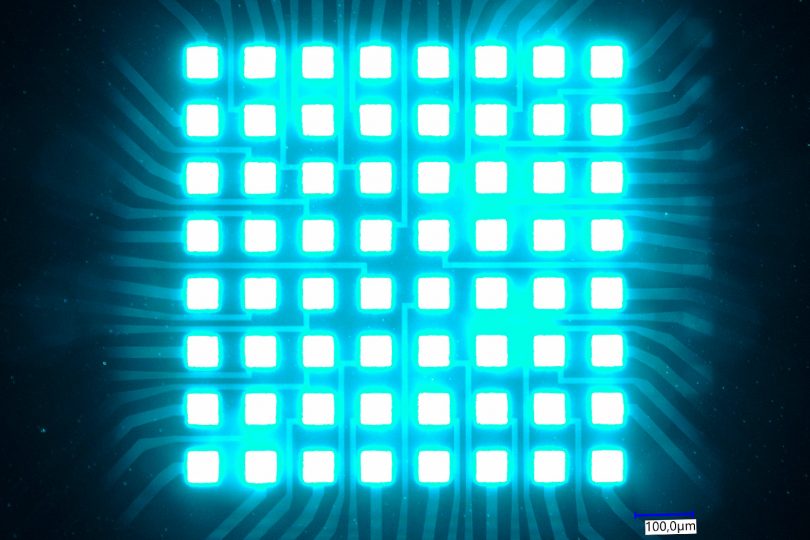

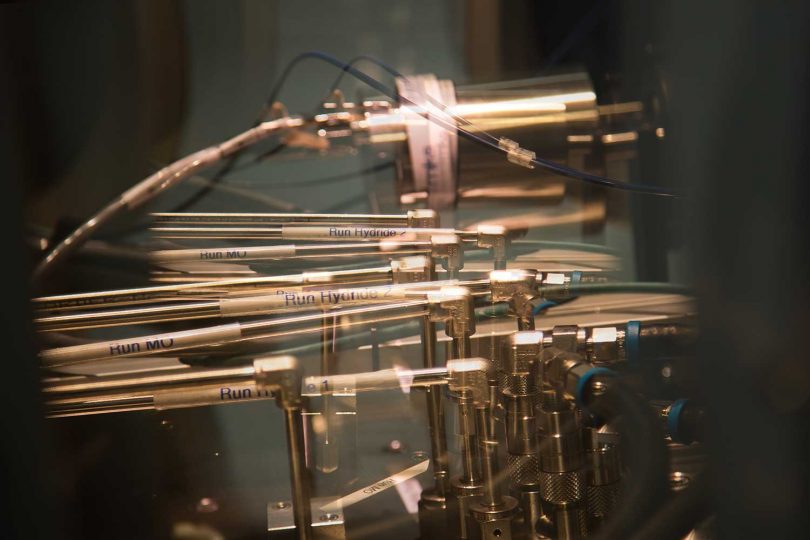

These are single atoms in the diamond, which we can read out as a team with lasers. Of particular interest to us is the spin (intrinsic angular momentum) of the associated electrons. We can use the spin to measure magnetic fields with great precision. As the smallest possible sensor, we can get particularly close to the fields we want to measure. So we are literally at the limit of what can be measured.

These sensors are potentially very versatile. On the one hand, they could be used to examine materials with special surfaces or very thin materials. On the other hand, quantum sensors are a leap forward in precision for life sciences. For example, in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), where the question is: What is the sample composed of? How high is the resolution? So far, an MRI works with millimetre resolution, and with a few tricks you get to about one hundred micrometres. But cells are typically only a few micrometres in size and molecules are about a thousand times smaller.

The researchers use individual atoms as quantum sensors in diamonds measuring just a few millimetres. Picture credits: Kristina Rottig/TU Braunschweig

This is where our quantum sensors come into play. With sensors on the atomic length scale, we can get as close as possible to the samples and then measure them very precisely. We then observe not only individual cells, but individual molecules, right down to the magnetic properties of individual atoms. We are just at the point where we are working towards application. The goal for the next ten years is to make this technology accessible to other disciplines such as chemistry, biology and materials science.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

I have always been interested in understanding how nature works. In addition, inspiration came from my personal background. My parents fled to Germany because we were persecuted and disadvantaged as part of the Islamic Ahmadiyya community in Pakistan. One member of this community was Professor Abdus Salam. He made it from a small village in what was then British India to world fame in science. He came to the prestigious Cambridge University for his studies and doctorate. In the years that followed, he developed a unified theory for the weak and electromagnetic interactions. For this he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. As a child growing up with a story like that, I always wanted to be a scientist like him.

At the beginning of my studies, it was not yet possible to foresee whether I could actually become a scientist. But when I learned that there are these individual atoms in diamonds that we could use as sensors, I got excited. It sounded like science fiction to me! This enthusiasm carried me from Mainz to Stuttgart to Harvard and now to Braunschweig.

What constitutes good teaching for you?

For me, good teaching is showing why a topic is exciting. Accordingly, I will look for references to current research in the lectures. In the winter semester, I’m holding a lecture on my topic, quantum sensor technology. There, we talk about the challenges that have to be overcome so that this field of research can be applied in practice. For this, we are going into the lab and look at experiments together. Furthermore, the students read and discuss current research literature. You first have to learn how to deal with scientific publications in order to understand the results bit by bit.