“I investigate the ground” Dr Matthias Bücker appointed Assistant Professor for Urban Geophysics

Matthias Bücker studied in Braunschweig until 2011, before completing a number of external placements in Mexico City, Bonn and Vienna. Finally, he returned to Braunschweig in 2018. Since January 2022, he has held the position of Junior Professor of Urban Geophysics at the Institute for Geophysics and Extraterrestrial Physics. There he leads a working group of the same name to develop methods for exploring the subsurface in urban areas. In the interview, he gives an insight into his research and his next projects.

Professor Matthias Bücker from the Institute for Geophysics and Extraterrestrial Physics. Photo credits: Markus Hörster/TU Braunschweig

Mr Bücker, what exactly do you deal with in your research?

As an applied geophysicist, I am in a way the radiologist among geoscientists. I develop and apply physical measurement methods that allow me to investigate the ground beneath our feet to make materials, structures or objects visible.

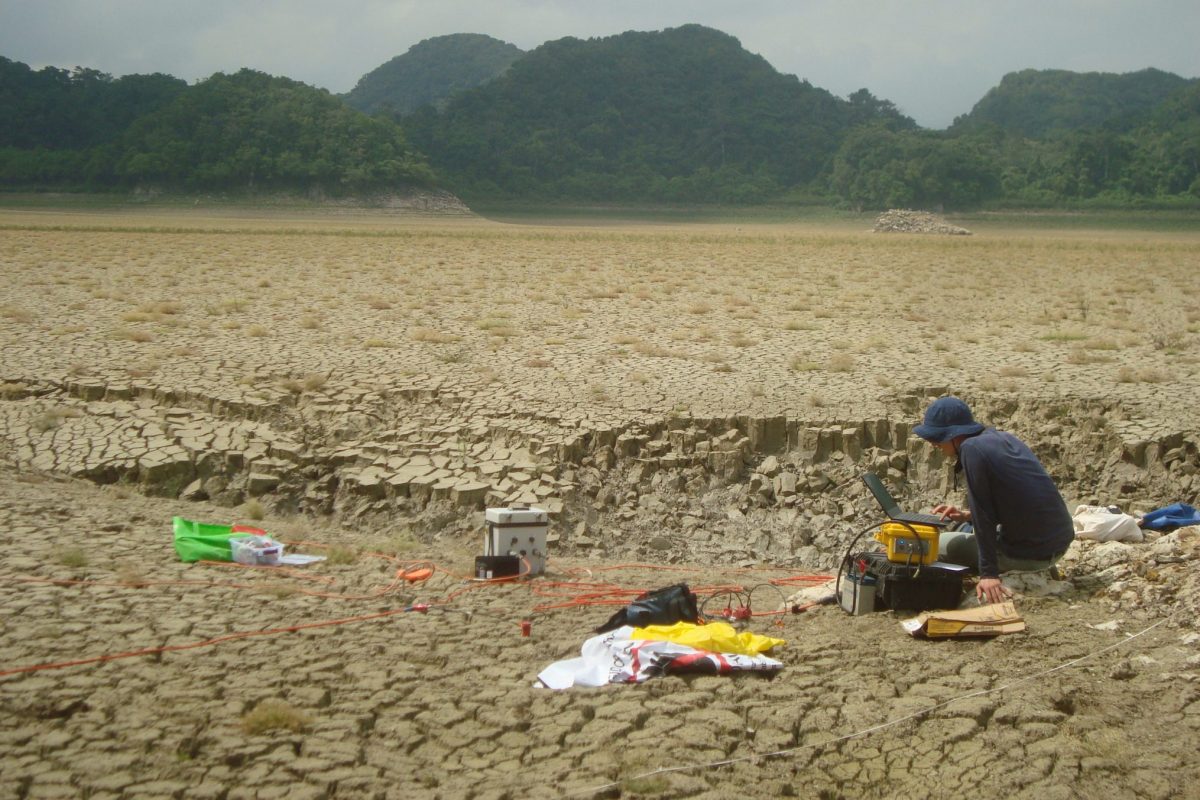

In my research, I mainly deal with methods based on measuring electrical conductivity. Because the different materials of the subsurface conduct electricity very differently, this material property is suitable, for example, for distinguishing layers of solid rock from those of loose sediment. In addition, as a good conductor of electricity, water strongly alters the electrical properties of the subsurface even in small quantities.

I have already applied these methods in the city and in the countryside, at icy heights in the Alps and in Tibet, on lakes in the Mexican jungle or old rubbish dumps. Many questions revolve around the issue of groundwater, which is sometimes frozen and sometimes polluted, which is lacking in one place and too much in another and then triggers dangerous landslides, for example.

What projects are coming up next?

In research, the first priority is questions that arise around the exploration of the underground in the city. A first exciting project that we have developed together with colleagues from the Institute of Geoecology and the Julius Kühn Institute will explore how urban green spaces can be used for climate-friendly urban development. Among other things, geophysics can provide important information about the availability of water at possible new tree locations.

With further small pilot projects in Braunschweig, we are also developing new interdisciplinary and interfaculty collaborations within the research focus Future City. For example, in a project initiated with the Institute of Geosystems and Bioindication and a local engineering firm, we will carry out measurements on Braunschweig’s Dowe Lake, which lies in the middle of an urban drinking water extraction area. Our measurements here will provide an insight into the sediment layers below the lake, which are important for its connection with the adjacent drinking water aquifer.

What motivates you to do research?

I find it fascinating to make things visible that would otherwise remain hidden. Moreover, the soil beneath our feet is a resource that is essential for our survival. It provides us with water. It also provides nutrients for the plants we feed on. It gives support to our buildings and, with the pipes and canals, protects the lifelines of our cities. Especially in the city, where many uses compete for the limited space – and water – underground, we need methods to make this resource visible and to then be able to manage it better.

What has been the best occurrence for you as a scientist at TU Braunschweig so far?

By far the best occurrence was being appointed as an assistant professor. This appointment closes a big circle for me: almost 19 years ago, I started here at TU Braunschweig as an architecture student. Although I later switched to physics, the topics of architecture and the city have never quite left me. In urban geophysics, there are now many exciting questions that require a close exchange with architects, civil engineers and people from many other disciplines.

And then it’s just particularly fortunate to have the opportunity to further develop my research in the long term with the assistant professorship. As a so-called double-career father – my wife, Liseth Pérez, also does research in the geosciences at the Institute of Geosystems and Bioindication – it also means that after many years of temporary contracts, at least one of us now has a predictable career perspective. As a family, we can be happy about that every day!

You have already experienced a lot at TU Braunschweig. What do you still wish for the future and which peaks will your path take you to?

In the Alps at over 3000 metres or even at over 5000 metres in Tibet, you work in a very special environment. The fieldwork focused on thick ice sheets and permafrost, which is ground that has been frozen for several years. But cities are also extreme places: For one thing, there is much more going on underground. For another, there are many disturbances that make the application of geophysical methods difficult and therefore demand a lot from us.

For the near future, I hope to be able to travel with a group of students to Mexico City in the summer – a megacity, by the way, that is also located at an altitude of over 2000 metres. There we want to combine geophysical and ecological studies under extreme urban conditions as part of an excursion organised together with my wife. In addition to the interesting geoscientific questions, I also consider getting to know other cultures and building international networks to be extremely important and motivating. You can’t start early enough during your studies!

What advice do you have for young researchers?

If you are passionate about your research, don’t give up too soon – even if the prospects often make you doubt it! As a dual-career couple, my wife and I especially advise this to all women in science. Sometimes a presumed weakness can unexpectedly become a strength. For example, shortly after my dissertation at the age of 36, I was afraid that I was getting too old for a career in research. I spent several years abroad, spent a lot of time with my children and worked on a lot of interesting research and industrial projects. All these things, which do not lead to a professorship by the straightest route, took time. In the end, however, it was precisely these experiences that prepared me for the assistant professorship in urban geophysics at TU Braunschweig.

Thank you for the interview.