Particulate matter measurement on the bike Masters student at TU Braunschweig continues development of OpenBikeSensor

Particulate matter, carbon dioxide and other airborne pollutants affect our health. But how can this pollution be made visible? Merle Riecke, an environmental engineering graduate from TU Braunschweig, has found a solution: a mobile measuring device that helps cyclists find clean routes. She developed the OpenBikeSensor as part of her master’s thesis at the Institute of Transport, Railway Construction and Operation (IVE).

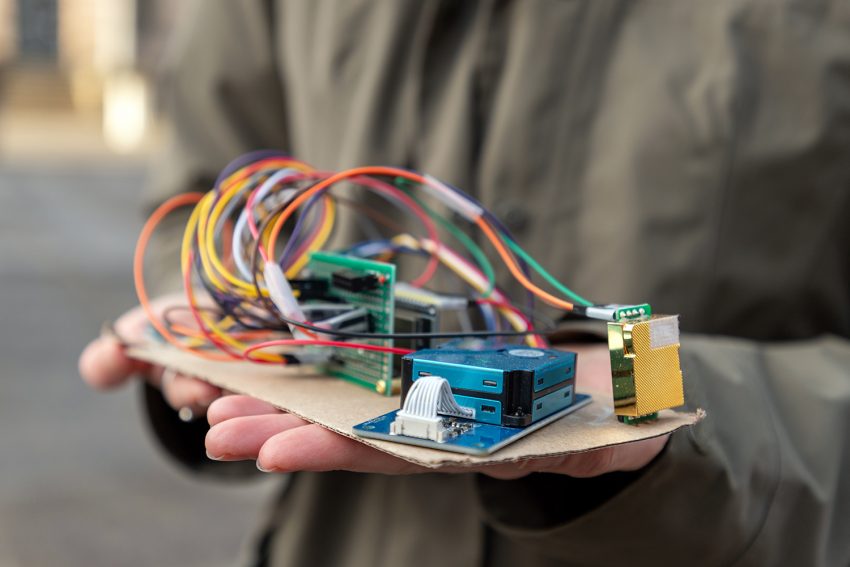

In her master’s thesis at the Institute of Transport, Railway Construction and Operation (IVE), Merle Riecke further developed the OpenBikeSensor by integrating a particulate matter sensor. Photo credit: Kristina Rottig/TU Braunschweig

At first glance, it looks like plain grey tube that Merle Riecke carries on the luggage rack of her bicycle. But inside is a whole range of technology: a particulate matter sensor that measures the particles in the air, two other sensors that measure temperature and carbon dioxide, a GPS module that assigns the measured values to their respective locations, and a controller. The environmental engineering student, who specialises in public transport and transport and infrastructure planning, built all this herself as part of her master’s thesis. Her goal: “The idea is that people can use the sensor to measure their daily journeys and see where they are most exposed.” In order to make her development accessible to as many people as possible, the TU student based her work on the OpenBikeSensor open source project. This is a sensor that you can build yourself, which is normally used to measure the overtaking distance of cars and helps to identify dangerous spots in urban traffic.

Merle Riecke realised early on that her idea to extend the sensor would be met with enthusiasm when she visited the “Maker Faire” in Hanover, a trade fair for tinkerers and technology enthusiasts. “Originally, I went there to find tips and tricks,” she says. So she was all the more surprised to get so much positive feedback on her project: “We didn’t have a moment’s peace. There was always someone at the stand who liked the project and had their own ideas.” For the student, this was confirmation that her project had struck a chord.

Cable tangle and first setbacks

But first the sensor had to be built. And that proved to be more complicated than expected. Riecke had to familiarise herself with microcontrollers, test sensors and write code. “I’m not a programmer, so I had to teach myself how to do everything” she says. Sometimes the values were wrong, sometimes a connection failed. She would spend hours trying to figure out why something was not working.

Merle Riecke designed the complex sensor herself and had to learn additional programming skills. Photo credit: Kristina Rottig/TU Braunschweig

But she kept at it. Little by little, the system became more stable. With the support of her brother, a computer scientist, and numerous experiments, she succeeded in developing the measuring device. “It was a lot of trial and error,” says the graduate. “But eventually it worked.”

Test drives between rural and urban traffic

When her prototype was ready, she began to test it. In the sparsely populated region of Lüchow-Dannenberg, where she lived while working on her master’s thesis, the air was good. Too good. “I wanted to take measurements that would show me where it’s really dirty,” says Riecke. So she drove to Lüneburg in the middle of rush hour. The sensor responded, but the readings were surprising. “The concentration was lower than expected,” she says. She suspected that the heavy rain that day had washed the particulates out of the air. It was only when she drove past a burning fire that the readings rose significantly, proving that the sensor was working. To get even more accurate readings, she also calibrated her sensors at an official measuring station in Braunschweig.

A project with potential

The sensor has now been built and the thesis successfully completed. However, the project could continue. The measured air quality data could be fed into a map that colour-codes particularly polluted routes so that cyclists can avoid them. In the long term, with even more data, the device could help cities and communities identify air pollution hotspots and take action. Other exciting ideas for developing the sensor came from the “Maker Faire”. “For example, there was an idea for the integration of a vibration sensor for the measurement of road conditions.” Riecke hopes that people or projects will be found to develop the project further and perhaps even merge it with the OpenBikeSensor.

Whether she will work on further development herself is unclear. For now, she is looking for a job. Merle Riecke would like to work in the field of public transport. Her dream is to make cities more environmentally friendly. “We only have this one world,” she says. “And I would like to do my bit to protect it.”