On an expedition to the lakes of the Maya Biogeoscientific study trip to the karst lakes of the tropical rainforest in southern Mexico

Surrounded by the jungle with its impressive vegetation and exotic animals, seven students had the opportunity to ecologically and geophysically investigate jungle lakes on a study trip. Along the way, they gained insights into the life of the Lacandons, who belong to the Mayan ethnic group, and were able to taste local culinary specialities. Students Bastian Brömer and Ruth Glebe report on the trip organised by Dr Liseth Pérez from the Institute of Geosystems and Bioindication and Professor Dr Matthias Bücker from the Institute for Geophysics and Extraterrestrial Physics.

View over Mexico City from the plane. Photo credit: Bastian Brömer/TU Braunschweig

Our study trip to the remote jungle area Selva Lacandona on the border to Guatemala began with a very long journey: We started by taking the plane from Frankfurt, continuing via Atlanta, USA, and Mexico City until reaching Villahermosa. Then we continued by minibus to Palenque, where we arrived after a total of 37 hours. Once we had arrived in the tropics, we were impressed by the unusual vegetation at the side of the road: in addition to the houseplants that are popular at home, which grow in the wild and much larger here, there were banana trees, palms and agaves to marvel at. The climate with very high humidity and lots of rain allows some plants (epiphytes) to thrive on tree branches and even on power lines.

- Palenque: In the foreground a pyramid, on the left as found, on the right excavated and restored. Photo credit: Ruth Glebe/TU Braunschweig

- Restoration work at a Maya temple in the jungle of Palenque. Photo credit: Ruth Glebe/TU Braunschweig

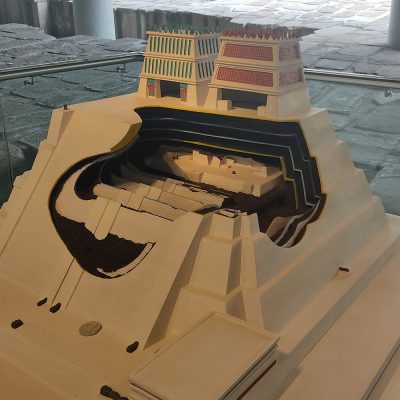

- Model of the Templo Mayor pyramid in Mexico City. Since each Aztec ruler wanted a larger pyramid, the existing pyramid was built over and enlarged. The model shows the different layers. Photo credit: Bastian Brömer/TU Braunschweig

After a night in modern Palenque, we drove to the archaeological site to visit the pre-Columbian Mayan metropolis of Palenque. There, more and more ancient pyramids are being uncovered and investigated in the jungle to this day. The pyramids of the Maya were for the most part solidly built. They were used as a base and to raise the mostly sacred buildings on their summits. Directly behind the pyramids, the rainforest stands like a green wall.

First caves, then lakes

Our next stop was in the highlands of the Selva Lacandona, the rainforest of the Lacandones. In this low mountain range, the subsoil consists mainly of limestone. The so-called karst is criss-crossed with caves and fissures. Penetrating water has eroded the limestone over centuries. If such caves collapse, lakes, so-called karst lakes, can form. We explored some of them in the following days.

The next nights we stayed in Nahá, a small jungle village. It served as a base from which we started the field measurements on the lakes. We were housed in the small huts of a hotel – with walls made of bamboo sticks and roofs made of roof tiles and palm leaves.

- In the tropical rain: The first measurement results are examined on Lake Tzibaná. Photo credit: Ruth Glebe/TU Braunschweig

- Besides work, pleasure was not to be neglected. Swimming in Lake Tzibaná. Photo credit: Ruth Glebe/TU Braunschweig

- On Lake Tzibaná, the sonar device is prepared for the geophysical measurements. Photo credit: Ruth Glebe/TU Braunschweig

Water Depth Charts and Sediment Samples

For our studies, we divided our group into two boats. From one of the boats we took sonar measurements to study the depth of the lakes and the bottom of the lake. In the evening, we were able to use the data obtained to create water depth maps, also called bathymetric maps. The crew of the second boat took water and sediment samples, which they analysed geochemically and for bioindicators. For the sampling, the information on water depth was important to find suitable sampling sites.

For the two lakes Tzibaná and Metzabok, samples had already been taken at earlier times. The comparison with our new data will allow us to derive statements about the temporal development of the lake’s water quality. On the third day, we explored a small lake in the village of Sibal, which provided a surprise: with its small diameter of only 50 metres, it has a depth of 30 metres in places.

The small lake in the village of Sibal. Local residents watch us take measurements. Photo credit: Bastian Brömer/TU Braunschweig

On the fourth and last day of measurements, Lake Guineo was on the agenda, also near the village of Sibal. As the lake is very large with an area of 2.36 square kilometres, we concentrated on measurements around a group of five small islands. On this day, we were accompanied by Josuhé Lozada, a Mexican archaeologist who wants to study the Maya ruins he discovered on the islands in the coming years. Josuhé reported that around 700 AD, the Maya had to retreat from the large cities in the lowlands – like Palenque – because there were several prolonged droughts. In the highlands of the Selva Lacandona there was still sufficient water; new settlements were founded here.

The water levels of the karst lakes were probably also lower at that time. Today’s islands were probably hills at that time, further fortified by the Maya into pyramid-like structures. When we stepped onto one of the islands, we also found hewn stones there. There are said to have been paved paths between the islands. With our sonar measurements, we actually found some striking structures. Josuhé and his team will conduct dives here next year, where our measurements will certainly help as an orientation.

Paintings of the ancient Maya at Lake Metzabok. The dog, as a human’s best friend, accompanies the souls into the underworld. Photo credit: Ruth Glebe/TU Braunschweig

“Not that poisonous”, unmistakable and beautiful fauna

On the way back to Villahermosa we made a detour to two more lakes. Again, we didn’t see any crocodiles, which we really wanted to spot, but at least we saw a turtle. We were spared snakes and scorpions on our trip, but a centipede sat in one of our beds, which according to the locals was “not thaaat poisonous”. But there were also beautiful animals to observe, including hummingbirds, dragonflies and butterflies. The howler monkeys, climbing high above our heads in the trees, were impossible to overlook or not hear.

- A look into the rain forest by Palenque. Photo credit: Ruth Glebe/TU Braunschweig

- This insect is drying its wings on the paddle after we rescued it from the water. Photo credit: Ruth Glebe/TU Braunschweig

- Hummingbirds were regularly seen at breakfast. This one is probably a Striped-throated Hummingbird. Photo credit: Ronja Schwenkler/TU Braunschweig

Loud farewell after the silence in the jungle

On our return journey via Mexico City, we visited the Templo Mayor, the ruins of a large pyramid in the centre of the former Aztec capital Tenochtitlán. In the evening we went to a typical Mexican cantina where many mariachi bands were playing – simultaneously. With the loud confusion, this farewell dinner in the capital was in great contrast to the days in the secluded jungle.

Dinner in the village of Metzabok. Hidden object: Who can find the family’s semi-tame parrot? Photo credit: Ruth Glebe/ TU Braunschweig

In the villages we ate in small restaurants. Often we were the only guests and sat in the living rooms of the families. Throughout the week, the menu consisted mainly of tortillas, beans and plantains, prepared and combined in many different ways. The families were extremely hospitable and willingly answered all our questions. We learned how they grow and prepare their coffee. They also told us about their semi-tame parrot that likes to have a sip of coffee in the morning.

Authors: Bastian Brömer und Ruth Glebe

Group photo in front of the temple ruins of Palenque. Photo credit: Ruth Glebe/TU Braunschweig